LXXII Generation Roman

2024

This was written for a book that developed out of a workshop given by Radim Peško at ISIA, an art school in Urbino, Italy, where I also teach. The project involved design students making digital typefaces based on the Roman captials on the facade of the Palazzo Ducale, a Renaissance building in the centre of town. The publication, Type and Context, is available from Roma Publications.

Lead image: Overlaid instances of the letter Z by three separate groups of students. The Z doesn't feature in the original inscription and so had to be extrapolated from the other characters.

*

While wondering what to write for this book I happened to listen to “Turn the Page,” the opening track on millennial UK garage/hip-hop/grime/pop act The Streets’ 2002 debut album Original Pirate Material. Amid the brag and bluster of what amounts to a kind of manifesto based on military metaphors, the protagonist declares:

I’m 45th generation Roman

But I don't know ’em or care when I'm spitting.

The duration of a human generation is generally considered to be around 20 –30 years, which is to say more or less the time it takes for one person to develop into a reasonably mature adult. Working backwards, then, The Streets place themselves as the latest cultural warriors on a trajectory that began sometime around (2002 AD – [45 × 25] 1,125 years =) 873 AD. Given that the Roman Empire is generally considered to have declined around 500 AD, the math is somewhat dubious, but you still get what the lyric wants to mean. It anyway got me wondering about what the line stretching backwards and forwards from the lettering on the facade of the Palazzo Ducale in Urbino might imply—made by members of the 72nd Generation Roman if you apply the same shaky calculus with a touch more accuracy.

I’ve been thinking a lot about generations lately, which I put down to the fact that I turned 50 last year. Considering cultural change in terms of generations always seems to me more relevant than chopping things up into decades—the sixties, the eighties, the aughts—as today’s mass media tend to prefer. It seems altogether too arbitrary. There’s a flexibility to the idea of a generation, as you can toggle the start and end date according to what it is you’re out to prove, and this grey area seems more faithful to the actual messiness of life.

A few months ago I ran a workshop for graphic design students in Zurich called “What do we think we’re doing?” We spent the first couple of days recording a discussion about their generation’s view of our shared vocation, then edited a transcription of it to make ourselves sound smarter, and spent the rest of the week translating it typographically onto the page in various ways.

In the hope of feeding the discussion, I had introduced the project on the first morning with reference to three examples of generational thinking in art and design. The first is an old favorite of mine, an article in the journal Typographica from 1967 called “Kurt Schwitters on a Time Chart” by the Polish polymath Stefan Themerson. This is a hybrid essay-biography-timeline based on a talk he gave about the itinerant German artist’s life and work to students in Cambridge seven years earlier. He began by drawing a timeline stretching from 1880 to 1960 on a blackboard, then added three dots. The first one marked when Schwitters was 20 in 1907, the second marked when he, Themerson, was 20 in 1930, and the third marked *now*—which is to say then, in 1960, when the students in the audience were 20. He writes:

20 is probably the time when the retina of our eye becomes tattooed with the picture of reference points from which we later measure different historical perspectives. Till we are 20, we depend on other people. They are therefore responsible for the world. At about 20, more and more people begin to depend on us. We are therefore responsible for the world.

We’re all used to considering art with regard to its original context, but Themerson goes a step further here, visualizing that context to such a memorable extent that his audience is effectively trapped. As the time chart materialises in front of them, there’s no way for them not to contextualize. You might say he resuscitates the idea, breathing new life into contextualizing in a way that’s both playful and provocative, not unlike Schwitters himself. “And the lines terrified them,” he recalls; “they suddenly realised that they were not set apart, not exempt, they suddenly saw themselves involved. Not ‘committed,’ just involved in the inescapable machinery of time that is swallowed up by shifting human lives.”

The second thing I brought up was the work of the British graphic designer and historian Richard Hollis, who combined these activities in a standard textbook on the matter, Graphic Design: A Concise History. Hollis says that graphic design can be considered in terms of three key aspects—social, technical, and aesthetic—but that far too much attention is devoted to the aesthetic at the expense of the other two. In which case you miss at least 66% of what’s instructive about any given piece of work. Indeed, the perennial problem with looking at reproductions of generations of graphic design in books, on websites, or projected onto a wall, rather than the original artefacts themselves, is that it’s by no means given that a viewer comprehends how it was made, or in what context. Both factors can significantly affect the way it looks, which is generally what we’re trying to understand in view of applying that intelligence to our own work. Without grasping the backstory, you tend to read the form as if it sprang fully formed from the designer’s mind—as an exercise in formalism to compare and contrast with, say, International Style, or Sister Corita Kent, or Memphis. This is what happens if you’re unable to adequately deconstruct the work, but by mentally dismantling a piece of graphic design you can understand how to do graphic design—and other things besides.

And the last thing I mentioned in Zurich was a recent essay, “Art! On the Underground,” by Zarina Muhammad, who is one half of the art-critical double-act The White Pube. Their approach has been described as “embodied criticism,” and this is a great example. Ruminating over the public function of the arts in Medieval Italy (funnily enough), Zarina finds herself on the Tube hallucinating in the Victoria Line’s oppressive heat, and encounters a number of ghosts from the past who were involved in similarly bringing art and design to public spaces during the twentieth century. These include London Transport’s own Chief Executive Frank Pick, who in the 1930s commissioned vanguard artists, graphic designers and architects to make work for the network—Harry Beck’s seminal map, Edward Johnston’s distinctive typeface and “roundel” symbol, Charles Holden’s station architecture, posters by such as Edward McKnight Kauffer, and murals by such as Eduardo Paolozzi, many of which remain in place today. Although the London Underground remains one of the few public institutions committed to commissioning art, The White Pube’s piece is a useful reminder of how social integration of the arts is a largely lapsed project, yet written in a propulsive way that makes you want to play a part in reactivating it again.

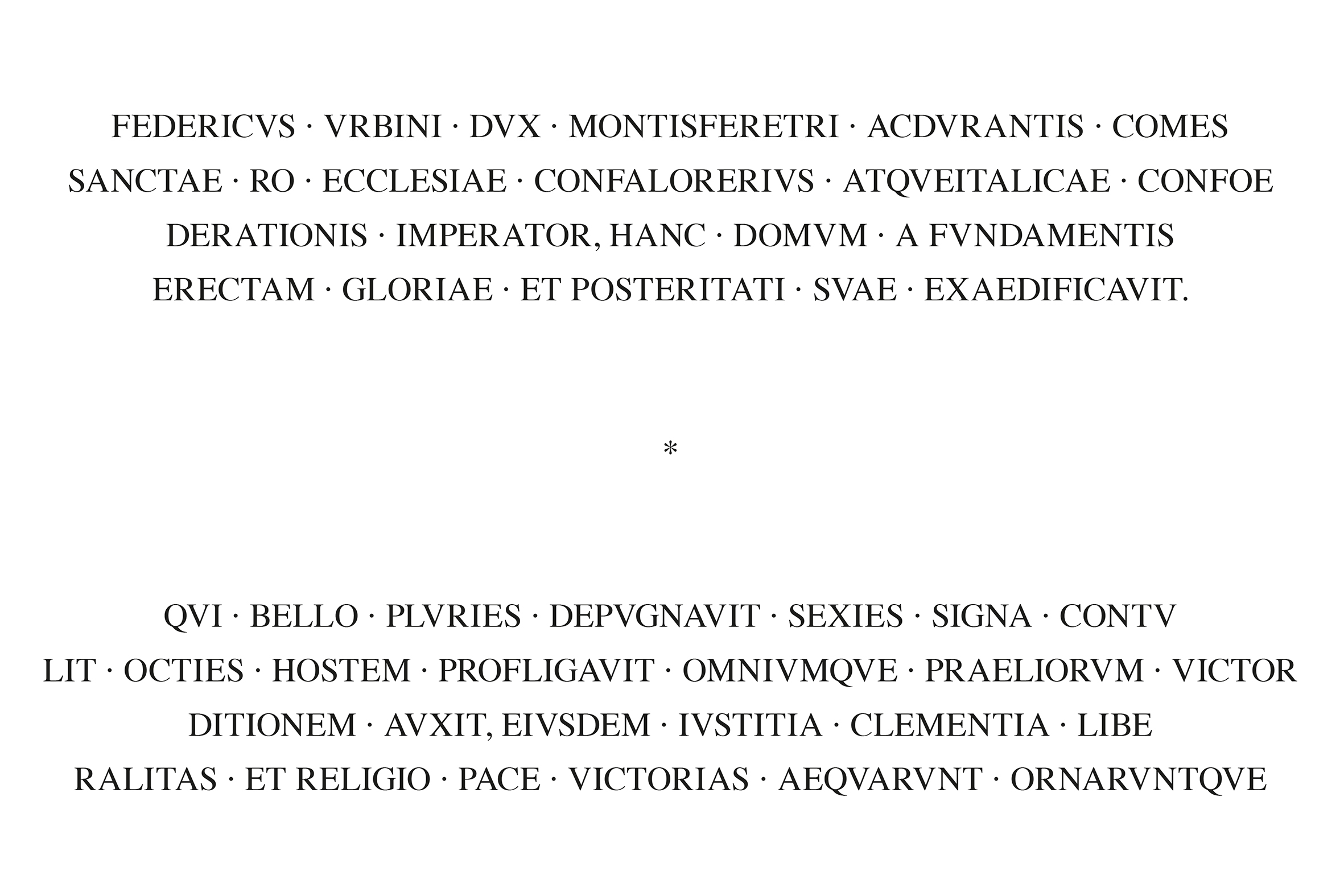

All three examples consider generational change relative to the arts—socially, technically, and aesthetically. With all this in mind, let’s now shift to Urbino and the lettering under consideration on the facade of the Palazzo Ducale, an inscription from circa 1500 AD that proclaims Duke Federico’s glory in battle, not unlike The Streets’ track. Let’s consider this the product of Generation R (for Renaissance). In line with the humanities of the time, they were already well into the concerted revival of Classical Antiquity generally, and the Roman Empire specifically. For the sake of convenience, we might date this around the height of the Roman Republic, say circa 100 AD, and therefore consider it the product of Generation RR (for Romulus & Remus). What Generation R is out to do is not merely revive but re-birth and ideally surpass, are the interlocking principles of logic, reason, beauty, geometry and so on, that will give rise to future Enlightenment.

And now leaping forward to 2024, the current student representatives of Generation Z are effectively looking back to Generation RR via the work of Generation R, to understand how and why those particular Roman capitals were inscribed in the first place, then revived in the second: for what purpose, based on what principles, with what tools, and to what effect. But the current generation’s objective is no longer simply to breathe new life into these letterforms. Rather, they are performing speculative operations on them, without any particular end in mind. They are wondering, for instance, how the same typeface changes if the guiding principle for dragging these alphabets into the digital realm is based on consistency between letterforms, as opposed to accentuating their eccentricities, as opposed to drawing out their main points of distinction. And in tandem with these formal considerations, what it might mean to develop such typefaces technologically, based on, say, automation, algorithms, or artificial intelligence. As such, their aims and intentions are less formal or straightforwardly social, more philosophical. They are searching for reasons to do things a certain way.

Around 1980, the computer scientist and mathematician Donald Knuth developed a piece of software called MetaFont, initially intended as a helper application for his popular typesetting system TeX. Instead of the usual limited family of fonts in a given typeface—bold, italic etc.—it was based on a higher-level “meta” set of parameters that more or less corresponded with the usual qualities that make up such a family, but which could be tweaked relative to each other to generate infinite variants based on a single skeleton alphabet. In this respect it was closer to calligraphy than to the ways typefaces are typically generated by outline vectors today. Knuth’s proposition was that a fundamental, mathematically-containable ur-alphabet predetermines all the possible ways in which it might be dressed, and he published his thinking while working on it.

Although an interesting early experiment in automated font design, beyond its satellite relation to TeX, MetaFont didn’t gain much traction, being too complex a technology for typographers to grasp and too irrelevant for computer scientists to bother with. However, the cognitive and computer scientist Douglas Hofstadter engaged in an friendly debate with Knuth in the pages of the journal Visible Language, and later acknowledged that the exchange sharpened his understanding of the challenges and potentials of AI in getting closer to human thinking. He challenged Knuth’s claim that the “intelligence” of a letterform is mathematically containable and so presupposes all other letters in the same font, because the computer’s notion is limited by its fixed set of parameters rooted in the past moment when it was programmed, whereas the human idea of what constitutes any given letterform is always liable to change in the future. The difference between the computational and human view lies precisely in this relative fixity and relative fluidity—the latter being the holy grail of AI.

A 1992 paper titled “Letter Spirit” by one of Hofstadter’s collaborators called Gary McGraw expands on this idea, purposefully investigating the potential of AI via the subtle complexities involved in designing a convincing typeface. He describes the development of an eponymous piece of software that aims to model how the 26 letters of the Roman alphabet can be rendered in a uniform style by taking one or more “seed” letters as a starting point, then generating the others in such a way that they share the same style, or spirit. The goal is to surpass what he calls the merely mechanical (fixed) form of reproduction native to MetaFont, by combining it with a higher-level conceptual (fluid) one.

The mechanical process takes recurring qualities (serifs, slant, stroke width, etc.) and merely repeats them in various predetermined combinations. As such, it is merely doing what computers have typically done better than humans thus far, i.e., performing rote calculations at lightning speed. The more elusive conceptual counterpart, on the other hand, would effectively push the boundaries of what might be considered consistent with the seed form, and is therefore closer to AI’s goal of approximating—and surpassing—the wilder areas of reason and unreason characteristic of human intelligence. Ultimately, the program needs to not merely generate myriad possible outcomes, but also apply some form of quality control in order to judge what might be considered more or less successful letters within the given font. The software needs to be critical of its own output.

McGraw considers the question, What is the letter “a”? Most people would probably say the letter “a” is a shape, he says, but it is more accurately an idea. Consider the fact that there are two widely accepted basic forms of a lower case “a”—one with a crossbar and overhanging hook, and one without. They are essentially different shapes, but most of us would accept that both equally conform to our idea of the letter “a.” Now imagine either of those “a”s made in different ways—as material or digital typefaces, or hand-drawn, or assembled from boxes—then how any any of those forms might be variously distorted or warped, intentionally or otherwise. You will surely conclude that there is a very broad gamut of what we might consider to be a plausible “a.”

Any given letter of any given typeface is a combination of such an idea (an “a”) with a specific style (Times New Roman). “Letter Spirit” tries to work out how a computer program might balance these entangled aspects in such a way as to generate a reasonable font. It sounds straightforward, but any type designer worth their salt will tell you otherwise. As McGraw writes, “stylistic qualities of one letter cannot usually be directly transferred to another, they must be slipped into variants of the ‘same type’ so they fit within the conceptual framework of the new letter without bending it beyond recognition.” This is the heart of the problem: the distinction between mechanical “transfer” and conceptual “slippage.” In short, the human idea of an “a” is anything a human considers to be an “a” at any given point in time.

Switching to capitals, imagine an axis on the computer/mechanical end of which is a set of coordinates that describes a capital “A,” and on the human/conceptual end of which allows for, say, a solid triangle, or further, an image of a mountain, or an apple, or a blank space where there used to be an “A.” It’s not to hard to imagine the idea of an “A” still being perceived in all instances. What might such an extended axis suggest in the realm of type design? How might an invisible vestige of an “A” be put to use?

In 2011 David Reinfurt and myself, under our working name Dexter Sinister, updated Knuth’s MetaFont to work on contemporary computers. We called this 2nd-generation version Meta-the-difference-between-the-two-Font, and have since used it in different ways in different contexts for a variety of reasons. But rather than generating infinite numbers of fonts, its main use has been as a catalyst to think about and around the philosophical implications of the fertile project that Knuth’s tinkering set in motion. For example, in an essay we wrote with almost the same title as McGraw’s, “Letter & Spirit,” we consider that question of relative fixity and fluidity in light of its juridical counterpart, the letter of the law versus the spirit of the law, as well as religious fundamentalism versus spiritual freedom, or in more general terms, chauvinism versus open-mindedness.

Hofstadter concluded that one of the best things that MetaFont might do is inspire readers to “chase after the intelligence of an alphabet,” and “yield new insights into the elusive ‘spirits’ that flit about so tantalisingly, hidden just behind those lovely shapes we call ‘letters’.” This is what I think the students are up to when looking up at the facade of the Palazzo Ducale in view of making digital equivalents of its alphabet, and I like to imagine an entire course, rather than a single project, dedicated to chasing that same alphabetic intelligence. This kind of work is fundamentally conjectural—constructive rather than reactive—and the outcomes are less tools for doing graphic design, more tools for thinking, and therefore tools for teaching. Tellingly, too, the lines of investigation sparked by MetaFont derive from domains outside type design itself—from computer science, mathematics, and cognitive psychology, which identified the very human sophistication of language as prime for a case study.

Let’s return to Themerson’s time-chart and stretch his thinking on a grander scale with the present project in mind, plotting Gen RR around 100 AD, Gen R around 1500 AD, and Gen Z around 2024 AD. Fundamentally, what is each generation out to achieve in their own particular moment?

Presumably, Gen RR were taking the written alphabet and reshaping it with carving tools on stone in the new technology of Roman capital letters in order to convey a monumental message with social and political heft, and to withstand the ravages of the future as far as possible. Gen R, on the other hand, were looking to revive the forms of the first with similar materials and tools in the general tenor of classical rigour, towards reinstating standards or ideals that had been eroded or forgotten in the intervening Dark Ages.

And Gen Z? It’s an open question, way more ambiguous in intent than the other two. I suspect they are seeking to work out precisely why they have the impulse to look to the past in order to look to the future so far as it can be imagined or intuited, and in doing so perhaps open up new possibilities. They are conducting cross-generational thought experiments in the spirit of “Letter Spirit,” like: how might AI be put to use developing letterforms, in what contexts, for what purposes, and to what ends? These seem to me to be questions worth worrying over—and one valuable side-effect of that philosophically-minded typography course I mentioned a couple of paragraphs ago would be to loosen the grip that (anti-)social and related media has on current generations, which locks us firmly into the present at the expense of considering past developments and future prospects. Such work works to cleave this axis open again.

*