Lower-case ethics

2012

This was a talk delivered at Museum Sztuki in Łodż, Poland, on 11 December, 2012, where it was meant to serve as a trailer for a retrospective of the Polish couple Stefan and Franciszka Themerson the following season. An edited version of the last part about the film Stefan Themerson & Language was then included in a catalogue accompanying that exhibition, “The Themersons and the Avant-Garde” (22 February – 5 May, 2013).

It is a sister piece to So-called Ephemera.

*

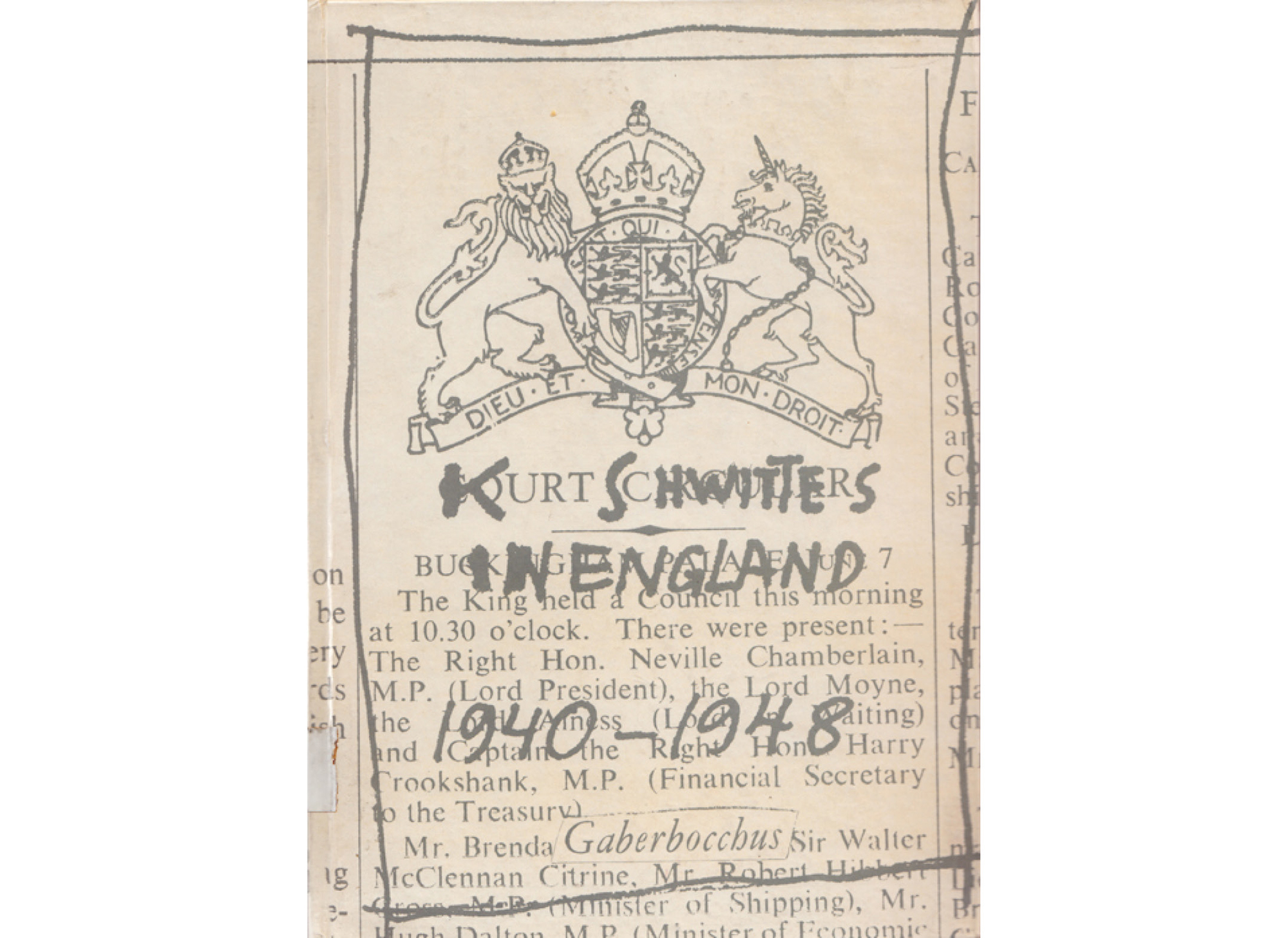

In Warsaw in the 1930s, they made a number of popular children’s books, as well as five avant-garde films before migrating first to Paris, then on to London during the war, where they remained for the rest of their lives—until 1988. They founded the fiercely independent Gaberbocchus Press in 1948 in order to publish their own work as well as that of like minds past and present, from Aesop and Alfred Jarry to Bertrand Russell and Raymond Queneau. For a couple of years from 1957, they also hosted an avant-garde literary den in their basement called the Common Room. So together they were also film-makers, publishers, and catalysts.

To avoid confusion, from now my “Themerson” will be shorthand for Stefan alone. I meant to do the whole thing using his Christian name, but recoil at the improper intimacy this suggests (the way some people refer to Warhol as “Andy”). I’m certain he would have disapproved too. For the time being, then, with no disrespect to Franciszka, Themerson refers exclusively to male of the species.

Specifically, I want to focus on Themerson’s ethics. I could maybe substitute “ethics” with “politics” or “social commitment,” but have to admit I don’t have enough of a grip on any of these terms to say for sure. What I can say for sure—because he said it—is that Themerson wasn’t interested in capital-E Ethics, by which he meant the academic discipline, only in lower-case-e ethical phenomena; that is, ethics as actually lived rather than abstractly theorized. Such was the crux of his work.

He was a steadfast pragmatist then – as long as you hear that as a common not a proper noun too, which is to say, nothing particularly to do with capital-P Pragmatist philosophy, nor for that matter with that eponymous brand of politics we’ve come to know since. In fact, if anything, you might say he was a lower-case-ist through and through. To quite literally perpetuate this line of thinking, I want to look at how this ethical orientation is manifest in his work. I don’t just mean how he explicated his approach to living in his writing, whether in his own talks and essays, or as channelled through his fictional or semi-fictional protagonists – where it’s always obvious enough; I mean to examine how this attitude comes across in less patent, more subterranean ways.

This attitude manifest amounts to what Walter Benjamin called ‘political tendency’. In 1936, Benjamin called for writers – and by implication artists generally – to further the cause of social and political progress not by merely writing to align themselves with one ideology or another, supporting a cause and thereby likely preaching to the converted, but by tinkering with and possibly subverting the root-level workings of their field. He wanted writers and artists to focus not merely on what they were writing and making and disseminating, but at least as much on how they were doing it.

By implicating themselves in this way, Benjamin said, writers could usefully work things out in public—a “working out” that both carries the work (propels it) and is carried in the form of the work (is reflected in it). For instance, a writer might observe that writing a certain kind of journal essay or a pamphlet is, to all intents and purpose, irrelevant or impotent, and so resolve to seek newly charged ways of writing and dispersing, of communicating-at-large— considering from scratch what they have to offer in view of the whole ecology of publishing, both within and beyond its conventions. Through this process of reflection and action, says Benjamin, the work will then inevitably manifest a political tendency. The writer doesn’t merely choose sides, left or right, but forges ahead by precarious example. In this way, his or her political alignment is actively refracted rather than passively reiterated.

I want to look at Themerson’s work through this ethical lens in order to draw out such tendencies in his own considerable body of work. If this seems contrived, it’s worth noting that he consistently and explicitly dealt with the subject of “ethics” himself—though never in a manner as dry as I’m making it sound. I’ll offer a few specific examples, and we’ll end by watching a film that features the man himself and hopefully embodies what I’m getting at.

…

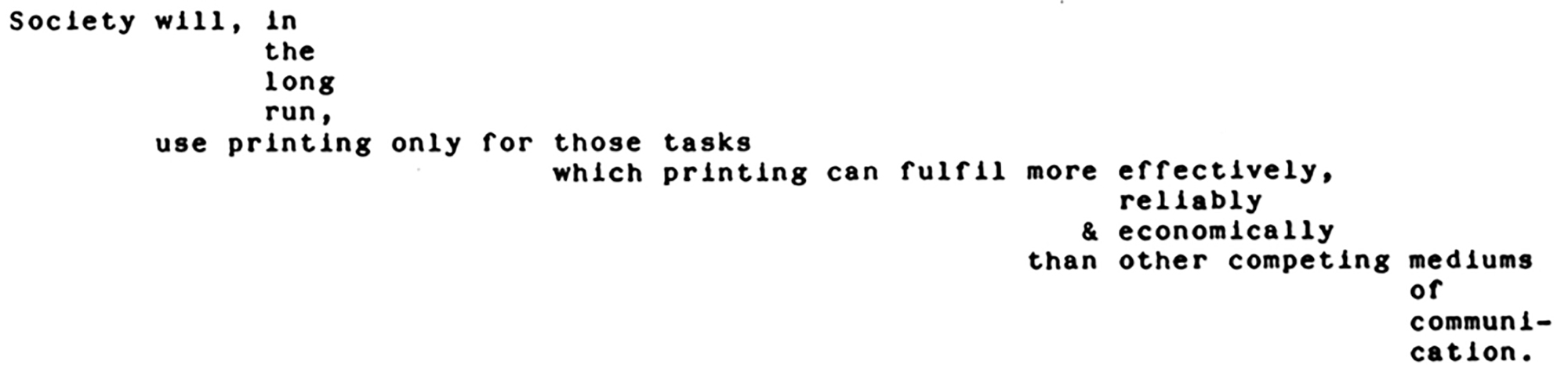

I first came across his work as an undergraduate studying Typography in the early 1990s. Flipping through a book called The Visible Word, I was arrested by a couple of pages of eccentrically-typeset text. This technique, I learned, was called Internal Vertical Justification, or IVJ for short.

As you can see, it involves arranging language in order to emphasize meaning—an extreme example of the project of typography generally. Paragraphs, sentences and words are carefully configured according to their relational grammatical sense. The Visible Word was a compendium of experiments that pushed the possibilities of verbal graphic language, but compared to the other examples, which I can only describe as more ‘academic’, it stood out as funny. Not laugh-out-loud funny, more a sort of winking—distinctly off, and so especially engaging. Also unlike most of the rest of the book, it worked; the method proved itself.

I later found out that Themerson had invented (if that’s the word) Internal Vertical Justification while learning English. When searching for the correct word to translate from Polish, he would list alternatives, then carry on with the sentence—a running Thesaurus. You can see the residue of that basic logic in its sophisticated development. At the time, this seemed even more instructive to me—that Themerson had taken a practical, mundane means for more efficiently learning a language, and transformed it into a more broadly operational proposal for more efficiently communicating ideas. As such, it’s one minor instance of what I think Benjamin was getting at – in this case, reflectively tinkering in the machine room of language, possibly in order to subvert it.

The lesson IVJ has to offer in the longer term is to show how verbal and graphic language – what it says and how it looks—can be productively conflated. That’s to say, it’s

two-fold

simultaneous

entwined

mutually-affecting

symbiotic

(though not without some obvious drawbacks, such as the space necessary; the real estate of the page.)

Anyway, IVJ lodged somewhere in my mind. I didn’t realize at the time it was only a gear in a much bigger machine, which I’ll come back to later.

Now, General Piesc is the title and protagonist of one of Themerson’s later short novels—just 54 pages—from 1976. (Could someone pronounce that for me …? That’s right—sounds like “punch” in English, and means “fist” in Polish: another symbiosis, in this case a multilingual one.) Having suddenly won a lot of money and become unwittingly liberated from his wife who’s run off with another man, this apparently discombobulated general sets out to fulfil a lifelong mission. Along the way he forgets the nature of that mission, at which point he finds happiness.

This brisk tale is mostly told through a handful of letters exchanged between the protagonist’s family and friends, the most consequential being a plea to the general from his daughter, a Princess Zuppa, that includes the following exhortation:

The Greek males thought geometry was the thing. Dr Zamenhof thought Esperanto was the thing. Jesus-Christ thought the dialectical loaf of bread was the thing. And geometry produced bazookas. And polyglotism produced more quarrels. And love produced hatred. And none of these great things has proved to be more (what is the right word) efficacious (?) than what I, in my female way, would like to call “good manners”.

I’ve put the paragraph up on the screen so you can witness the character questioning herself in the last line—worrying over the word “efficacious,” just like Themerson deliberating the exactitude of alternatives from his Polish-English Thesaurus. Note that she/he is careful to choose the correct word as well as point to her/himself carefully choosing. I take this as part of the point: that worrying over nuance, the concern to communicate correctly, is itself a very good-mannered, perhaps even the “female” thing to do.

Now I’ve always considered this statement profoundly modernist, though not in a sense particularly congruent with what most people take ‘modernism’ to mean. What I mean is nothing to do with neoplastics or international styles or any other brand of formalism. It is, however, in line with what was once called “the modern movement,” which I personally read as shorthand for an attitude or set of attitudes in advance of form; attitudes that fundamentally resist hardening into

rules

doctrines

ideologies

dogmas

absolutes

In other words, a state of mind perpetually oriented towards breaking from what Themerson once called ‘customary modes of thought’, that embraces—attempts to embrace—contingencies, particularities and exceptions.

Moreover, these are qualities native to the literary form of the essay, which literally means “attempt”—to some extent, then, a making-it-up-as-you-go-along, a reaching. According to T.W. Adorno (who wrote an essay about it), the procedural logic of the essay is “comparable to the behaviour of a man who is obliged, in a foreign country, to speak that country’s language instead of patching it together from its elements, as he did in school.” Here’s another fragment:

He will read without a dictionary. If he has looked at the same word thirty times, in constantly changing contexts, he has a clearer grasp of it than he would if he looked up all the word’s meanings; meanings that are generally too vague in view of the nuances that the context establishes in every individual case, just as such learning remains exposed to error, so does the essay as form; it must pay for its affinity with open intellectual experience by the lack of security … [As such] The essay becomes true in its progress, which drives it beyond itself, and not in a hoarding obsession with fundamentals.

Returning to General Piesc, it gradually dawns on the reader that the general’s ‘mission’ is some such fundamental goal, some heroic sacrifice or other, and one that the princess is trying desperately to divert by awakening in him a let’s say pointedly freewheeling attitude instead. “You see,” she says,

we don’t want saviours anymore. All saviours disrupt normal evolutionary processes, which anyway will go their own way. The way may be tragic … But what saviours do when they start meddling with it, is to make the tragedy still more painful.

In conclusion, she asserts that “all ideologies, all missions, all (capital-A) Aims corrupt good manners.”

In his hysterical analysis of historical models, Themerson notes that the Greeks’, Christ’s, Zamenhof’s and Marx’s plans for progress all are founded on Saving Graces and Big Ideas, that these Savers are invariably men, and that the premise of the Big Idea is always conceived in view of end results: once achieved the rest will fall into place. Problem solved: end of story.

On the contrary, Themerson’s female “good manners” are always contingent—radically contingent—because the efficacy of whatever deed is always relative; it always hinges on the specific circumstances. It’s not always good manners to help old ladies across roads, only particular old ladies who want to cross particular roads. Real good manners, then, don’t take the form of axiomatic aims, but bunches of habits, which we could sum up as a

demeanour

disposition

bearing

temperament

inclination

When I first read Themerson’s “good manners” as an infant graphic designer, I understood it, obscurely, as a maxim for designing, for organizing stuff with intelligence. The idea seemed to tally with certain pedagogical platitudes: work without preconceptions … meet the limits of the brief … resist stylistic fashions … let the content speak … and so on. That’s what that modern movement means to me: strictly movement: a thinking-on-your-feet and a keeping-on-your-toes.

Themerson’s other novels are likewise full of such ethical insight, sharp and blunt at the same time.

In the perpetual attempt to say it more carefully, more precisely, he induces the reader on the other end to think more carefully, more precisely. Themerson teaches by example: considerateness is passed on by osmosis.

There’s a theory about language you hear a lot these days that goes something like this: Because we know the world through language, as the nuances of language get eroded, limited, simplified, dumbed-down, it follows that our interface with the world, and so our experience of it, will follow suit. In other words, it will become

impoverished

bland

monotonous

one-dimensional

wasted

If these sentiments sound familiar, you’re probably remembering a well-known essay from 1946 by George Orwell called “Politics and the English Language.” Like Themerson’s, Orwell performs his opinions with alacrity. “Most people who bother with the matter at all” he writes, “would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot … do anything about it.” This fatalist point of view says: “Our civilization is decadent and our language must inevitably share in the general collapse.” He goes on:

it is clear that the decline of a language must ultimately have political and economic causes ... But an effect can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form … A man may take to drink because he feels himself to be a failure, and then fail all the more completely because he drinks … [The same thing is] happening to the English language. It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.

Orwell’s point is that this process is not inevitable but actively reversible. Modern English is full of bad habits, he says, ‘which can be avoided if one is willing to take the necessary trouble … to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way around” In fact, he continues, “It is probably a good idea to put off using words as long as possible and get one’s meaning as clear as one can through pictures and sensations.” Then afterward, “one can choose—not simply accept—the phrases that will best cover the meaning ….” Finally, he says that although his suggestions may sound elementary, in fact they require “a deep change of attitude in anyone who has grown used to writing in the style now fashionable.”

Writing in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, Orwell’s point is political as well as literary, and, true to his text, he makes this perfectly clear: “If one gets rid of these habits one can think more clearly, and to think clearly is a necessary first step toward political regeneration.”

Themerson dealt with ethics most directly in one of his latest pieces of work, a 1981 lecture titled “The Chair of Decency.” In it, he elucidates Princess Zuppa’s allusion that good manners are categorically female. The talk’s key idea is that, contrary to received wisdom, man is a biologically gentle species, (benevolent, altruistic, loving) who turns aggressive (vicious, corrupt, savage) through cultural influence. He supports the hypothesis by pointing out the fairly foolproof evidence that mothers don’t eat their children, which he calls “innate decency.”

A friend recently wrote to me about the critical theory’s relationship to the notion of change. She wrote that social or political theory as conceived by, say, the Frankfurt School (i.e., the Marxist critical theory that was practiced by Benjamin and continued by Adorno, among others) involves reflecting on a given condition in order to suggest a solution that’s designed to improve that condition. This sounds reasonable and obvious enough: illness, examination, diagnosis, prescription, health.

However, Gilles Deleuze considers this way of conceiving the world exactly the wrong way round, because it implies that the default condition is stasis where the real constant is in fact change. From this inverted critical perspective, then, the aim is to consider how and why things resist the natural flow of change, then work to remove whatever blockage. I’m simplifying wildly, but what’s instructive in terms of Themerson and ethics, is that Deleuze rethinks political or personal agency away from anticipating ideal outcomes and towards altering ongoing habits. Themerson put it this way: ‘in this changing world, the way from premises to conclusions is temporal and stormy, and you can’t force your Yesterday upon your grandson’s Tomorrow’.

This adds up to Themerson’s formula that “means are more important than aims”—that ways of going about things (naturally decent ways) are ultimately more important than what is done. “There do exist tragic situations when wicked means have to be used to suppress some other wicked means,” he admits; “but to use wicked means to promote aims—defeats the aims.” It short-circuits them. (To step out of the abstraction for a moment, you only have to think of how wicked means have been used to promote the aims of certain foreign policies in the past decade to see what he’s getting at. He’s talking about the sort of hypocrisy that has very real effects on very many lives.)

Which brings us to a lovely elliptical motto at the heart of his talk: decency of means is the aim of aims. If you stare at it long enough you’ll see this is a recursive sentence—not unlike “this sentence is a lie.” In fact, it has to be a recursive sentence in order to aptly embody itself, i.e., to remain perpetually active. It’s a sentence that refuses to settle, but that doesn’t mean you can’t glimpse its meaning.

…

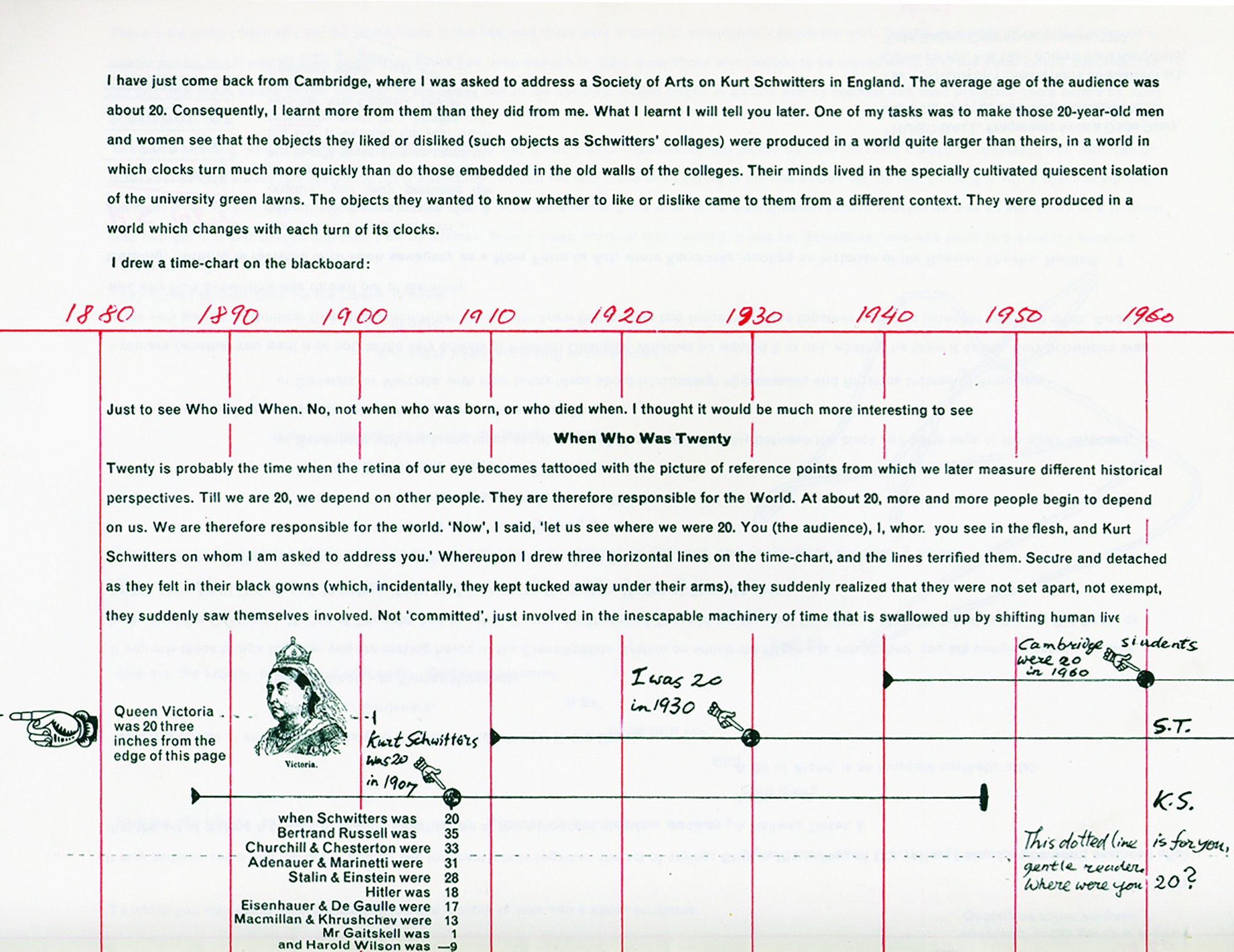

Next, I want to discuss something between an essay, a diagram, and a timeline called “Kurt Schwitters on a Time Chart.” It’s Themerson’s visualization of the German dadaist’s work relative to what was going on in the world before, during, and after it was made. They met by accident at a conference in London in 1943. Themerson was preoccupied by Schwitters fiddling with a piece of bent metal during the lectures. They started talking, discovered they were fellow intellectuals and creative independents, and remained in close correspondence until Schwitters’ death five years later.

What I want to emphasize is that as well as being a piece of history, the time chart itself has a long history, and that this history is folded into its evolving form. It started life as “Schwitters’ Last Notebook,” an informal talk that Themerson gave at the Common Room in 1958, a decade after the artist’s death, probably to a bunch of people not unlike ourselves who had gathered to look and think about someone else’s work.

Later the same year, a rewritten version of the talk was the basis for this Gaberbocchus publication, Kurt Schwitters in England, combined with reproductions of Schwitters’ collages, poetry and prose to form a particularly tactile object—a visibly spirited, knockabout kind of a monograph.

Then, three years later in 1961, Themerson prepared a revised version of the talk, presented in a more formal setting to a group of 20-year-old students in Cambridge. After a brief introduction, he drew a time-line on an overhead projector, then plotted three dots. The first one marked when Schwitters was 20 (in 1907). The second one marked when Themerson himself was 20 (in 1930). And the last one marked now, today—meaning then, in 1960—when the audience were 20.

He later recalled the apparent force with which the normally passive, detached students seemed suddenly thrown into time: “history” was now alive, activated, and they were accordingly implicated, involved. (Just as we are tonight, too—all variously 20 somewhere around here, off the edge of the chart, and even further along tonight.) As the talk proceeded, Themerson continued adding elements to the chart, gradually assembling the broader cultural context in which Schwitters made his work.

We’re all used to considering art in regard to its original context, to the extent that it would be impertinent not to at least pretend to do so. But Themerson goes a step further here, visualizing it to such a degree that his audience is effectively trapped: as this map materializes live before you, there’s no way not to “contextualize.” You might say he resuscitates the idea—breathes new life into “contextualizing” in a way that’s both provocative and playful. Not unlike his subject.

Themerson had good reasons for doing so. He reminds the audience of the horrific crucible (“that bloody stinking pit of European history nobody wants to remember”) in which Schwitters’ frequently delicate and beautiful work was concocted. He also shows how the work changed and continues to change according to when and where and how it’s seen.

The time chart is a collage, Schwitters’ own medium of choice (or circumstance): discrete found elements reassembled to form a new whole, the graphic equivalent of how Adorno describes the essay form. What ought to be apparent, though, is that what’s going on here is not a simple aping of Schwitters’ style, but a complex extension of his spirit.

But I’m getting ahead of myself, because what you’ve been looking at is not the acetate drawn and projected at Cambridge, but a later graphic translation of the same. If the Common Room talk was the first iteration, the England book the second, and the Cambridge lecture the third, this is the fourth, prepared some six weeks after the lecture but only published six years later, in 1967—and then only just, as the last piece in the last issue of an 18-year old magazine called Typographica.

The chart was configured to scroll at 90 degrees through the magazine’s A4 portrait pages in red and black ink. Themerson’s first draft ran to 28 pages, which was almost double the editor’s offer of 16, so it had to be cut back to 20, presumably with much difficulty and negotiation. Given the technology of the time, assembling this thing for print was no straightforward task. This only makes what I consider a masterpiece lecture in plan view even more impressive; but in a letter accompanying the artwork, Themerson wrote:

Here it is. And I am horrified. I have read it again, and I hate every word of it … What I would really have liked—well, I would have liked to be able to enjoy Kurt Schwitters’ work lightly, for the “pleasure it gives to the eye.” And yet I couldn't write it in that key. It's wrong, possibly, nevertheless it irritates me when I see people handling a collage by Schwitters as if it were a bunch of lovely flowers.

He added that the editor could print this disclaimer a post-script to the chart—but it seems they really had run out of space, or time, as it didn’t appear in the version eventually published.

…

In a few minutes we’re going to finish with a 40-minute film made for Dutch TV, directed by Erik van Zuylen in 1976. Zuylen also wrote the script, though it’s mostly based on Themerson’s writings. A 66-year-old Stefan stars in it as actor and interlocutor.

The film needs a bit of prefacing for a few reasons. Foremost, because it’s often difficult to make out what's being said. This is the effect of heavy Polish and Dutch accents speaking English, compounded by a general stiltedness arising from the fact that much of the time the players are visibly reading from a script. There’s a lot of noise in the signal, then, but there’s also a certain amount of self-reflexivity and time-travel at play too, and while understanding the references is by no means essential to enjoying what’s going on, I’m pretty sure that at least some background knowledge makes the whole thing less baffling. Trust me, I’m trying my hardest here to feed you only enough for starters that you remain hungry for the main course.

The film is in three parts. The first takes place on or around a bandstand in Amsterdam’s Vondelpark; the second comprises an interview with a spectacularly annoying professional orator; the third involves a walk along a very windy beach, during which Themerson continues to be interrogated by a sort of personal “policeman” played by Dutch neo-Dadaist Wim T. Schippers. Of these three, only the opening scene in the park requires elucidation.

One of Themerson’s earliest books from 1949, Bayamus, is an absurdist skit. The philosopher Bertrand Russell called it “nearly as mad as the world.” In it, a vaguely autobiographical protagonist meets the character Bayamus who—this will give you some idea of the tone—skates around London on a genetically evolved roller-skate at the end of his third leg. The narrator recounts his journey, under the direction of Bayamus, to a lecture at the Theatre of Semantic Poetry, the nature of which is as mysterious to the narrator as it is to the reader. About three-quarters of the way through the tale, he is met at the entrance of this Theatre by two well-dressed gentlemen and, to his surprise, led up onto the stage, where it gradually dawns, with understandable discomfort, that he’s the one expected to give the lecture.

This is the point at which we enter the film—with the added twist that Themerson the author is playing the role of his protagonist double some 26 years after writing and publishing him.

Now—again just to be clear—this ‘Semantic Poetry’ was something that Themerson had, in his own words (or something like them, as I’ve never been able to relocate the source), “invented using a machine made from certain parts of my brain”; and Bayamus was one of several vehicles he used to demonstrate its efficacy. It’s a literary method that subverts existing forms of language, typically poems or songs, by replacing the original words with precise—that’s extremely, absurdly, sarcastically, righteously precise—dictionary definitions. Themerson semantically translates, then, in the sense that he extracts strangely exact meanings from vague clichéd allusions. The method is usually demonstrated by comparing existing poems or songs with a semantically translated version. Again you’ll notice the line back to Themerson grappling with his Polish-English dictionaries and thesauruses, the toolboxes of language.

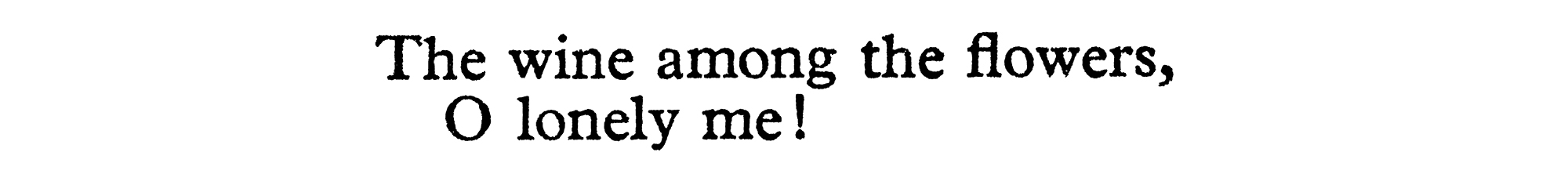

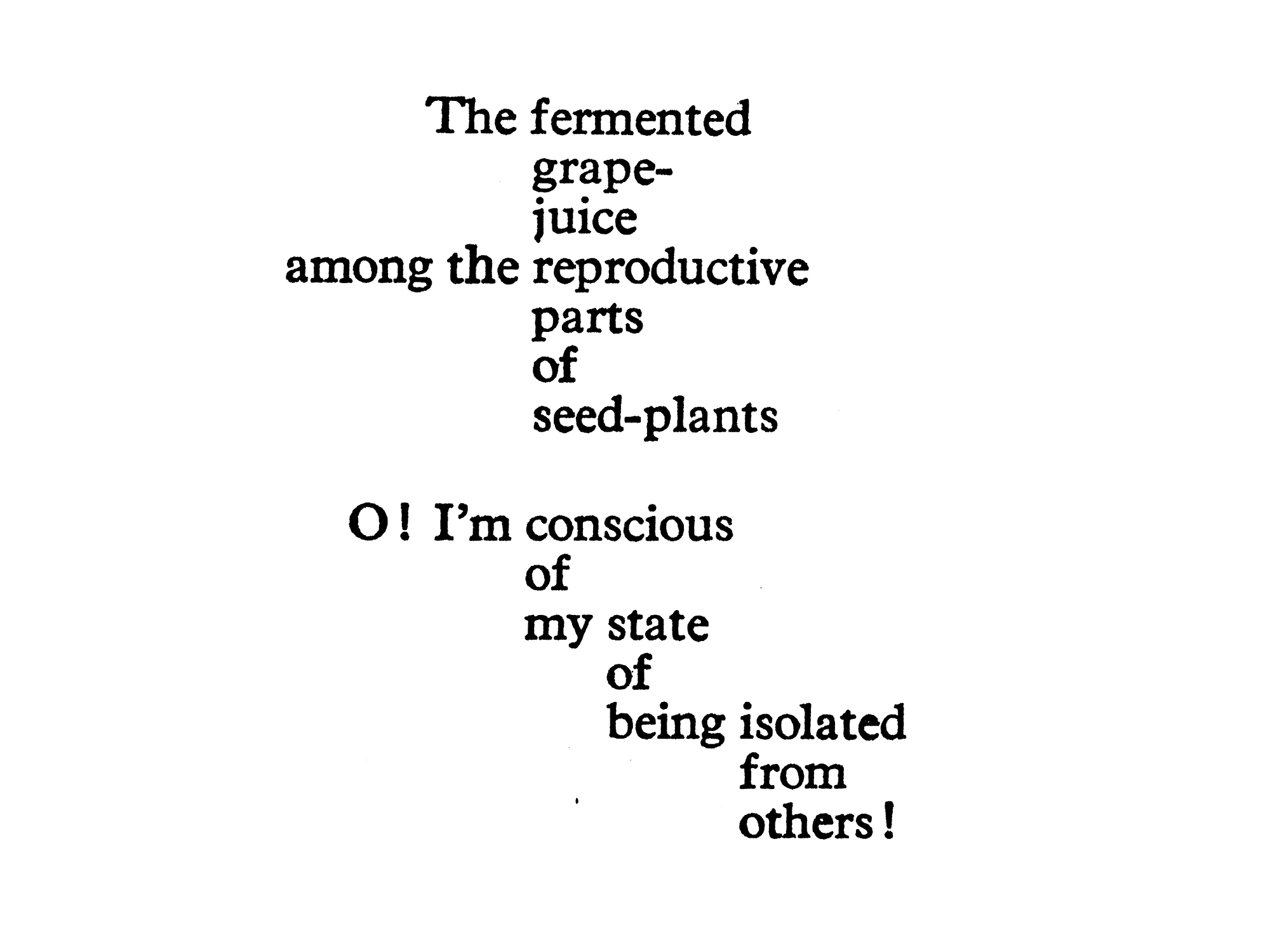

For example, from this:

to this:

Semantic Translation is more double-edged than this brief description suggests. Although it’s ostensibly an attempt to reclaim the “truth” behind words, the proposition is essentially ironic, not proselytizing. It’s more accurate to say that at best “truths” are more properly “beliefs,” and that beliefs should be treated with the utmost suspicion. One of the great benefits of the technique is that it reminds us how “the world is more complicated than the language we use to talk about it.” The nature of reading through the pedantic extent of a piece of Semantic Translation is to experience language made strange, to perceive both its technical depth along with its limitations. Themerson referred to this as “scratching the form to reveal the content.”

On one hand Semantic Translation is very funny—albeit what he calls “a poker-faced kind of humour,” which points to the fact that, as usual, Themerson’s intentions are as serious as they are comic. Semantic Poetry Translation was his brain-machine’s natural reaction to political demagoguery. It called attention to the fact that politicians had latterly begun appropriating poetry’s means—rhyme, syntax, repetition, alliteration and other tools of such as Themerson’s trade—to dubious or downright evil ends, variously intoxicating or lulling public minds into potentially pernicious “customary modes of thought.” As such, Themerson isn’t making a serious plea for linguistic reform, as Orwell was, but rather a hysterical, satirical, political gesture: a fist and a punch.

I said near the beginning that I’d return to that typographic technique of Themerson’s, Internal Vertical Justification, and here it is. Although he pulls pedantic definitions out of words throughout the story, and his writing generally has a similar technical precision, Semantic Poetry is always organized according to the eccentric but entirely meaningful logic of IVJ: “IVJ for SPT,” as he nicely abbreviates it in the book. There’s nothing stopping anyone writing or typesetting such a semantic translation in continuous lines—except common sense, because, as you can imagine, it would be very difficult to read or comprehend. There’s something else going on here too, to do with horizontal harmonies and vertical chords, but the film explains all that well enough.

The various genealogies of work I’ve recounted here manifest a self-critical spirit, a propensity to change. Ideas are perpetually revisited, revised, refined, but never merely recycled, always strictly transformed. The body of work has a life of its own. Themerson was vehemently against the sort of literary biography that joins the dots between a few loose anecdotes about an artist’s life and a few concrete pieces of work, and I think this is because, to an unusual degree, he’s very palpably in the work already. If you’re looking to the art for any insight on the life of the artist, then you’re looking in precisely the wrong place. “Bibliography is my biography,” he once said. Meaning: anything of consequence for anyone else is strictly in the work; all else is superfluous.

Back at the start I said my task was to look at how Themerson’s ethics “come across in less blatant ways” than in his writing. Here’s a by no means absolute summation:

First, in Gaberbocchus’ loose, knockabout publishing program, which was equally happy putting out eccentric children’s books, surreal novels, philosophical cartoons, and pointed memoirs. One fan noted that there’s “a madness about various Gaberbocchus books which is the spice of life, an ingredient somewhat lacking in the world of (most) book production.”

Second, in the particular brand of serious humour—perhaps not far removed from that madness—that infected, and still infects, pretty much everything Themerson made.

Third, in the readiness to work outside received wisdom—not for the sake of being different or new, but certainly to interrogate those “conventional modes of thought” that if unchecked might turn malign.

Fourth, in the agility to hop across—or flat-out ignore—disciplinary boundaries, and otherwise eschew categories or classifications generally.

Fifth, in the way the work is well-adjusted; meaning, aware of its audience and pitched accordingly, yet without ever toning down its essential anarchy. (A quick flip through any of their children’s books proves this point.)

Sixth, in the modesty and self-criticality that led to certain works being reworked, refined over time: a perennially active flow of thought, now and then made public in presentations and objects.

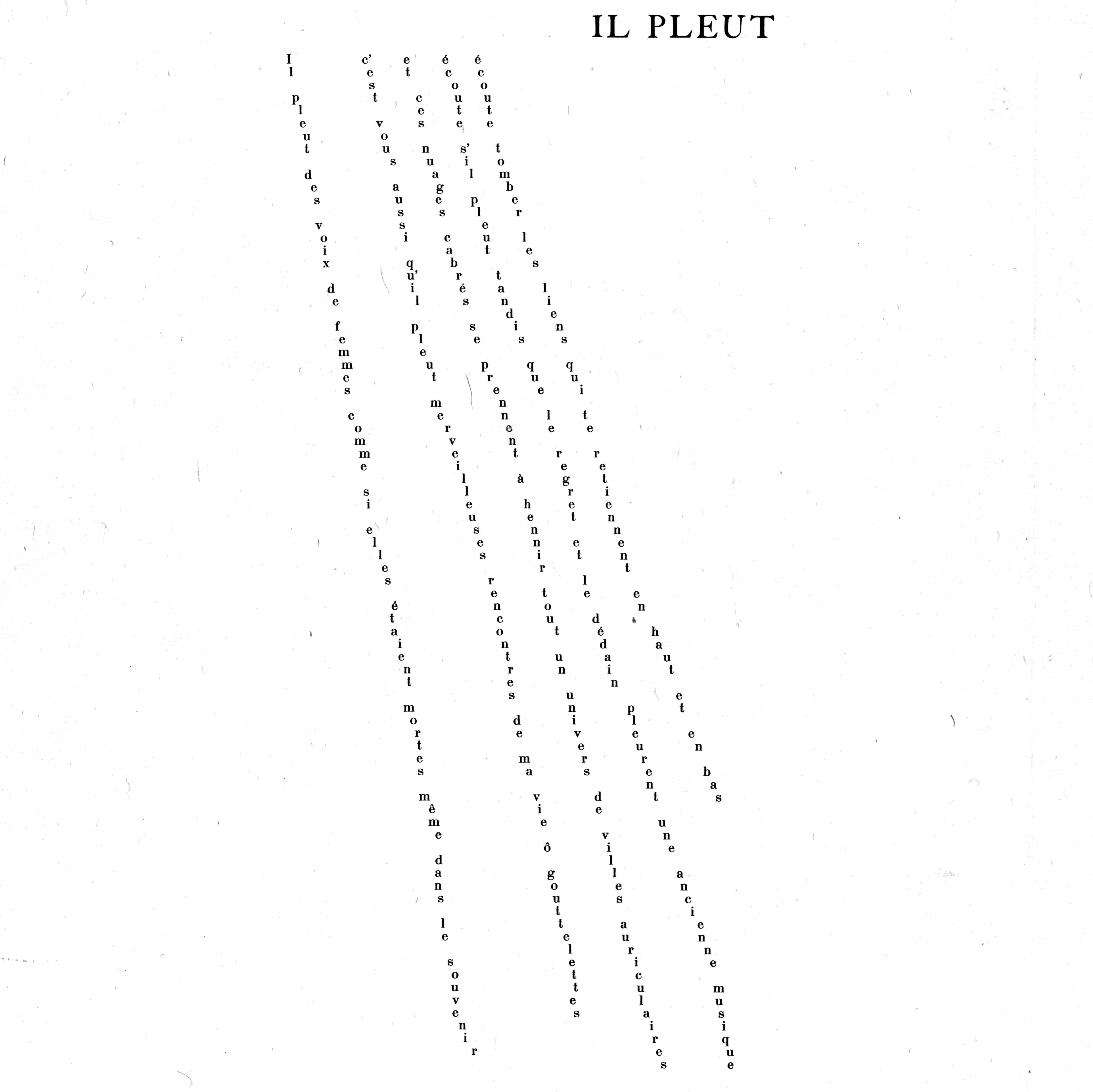

You’re probably all familiar with this poem, “Il Pleut,” the well-known calligram by 19th-century French poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Themerson was a huge fan, and wrote an exemplary essay on his work. I’m ending on this image (or is it text?), as a mascot-of-sorts for the talk, because the calligram, as you know, is a poetic form whose meaning and appearance are tautologous, one and the same: the arrangement of the letters of a poem about rain that form the image of rain.

I put it to you, then, that it’s no surprise Themerson was so fond of the calligrams, because what he’s after ethically is precisely in line with what Apollinaire achieves aesthetically. What I mean is, as a generic form—as a “type”—the calligram is useful shorthand for practising what you preach … which, in doing so doesn’t seem to preach at all. Better yet: it cuts out the need for preaching altogether.

As a case in point, then, let’s watch Van Zuylen’s film, which you’ll see is a very odd creature. When the director first proposed the idea, Themerson refused; not least, apparently, because the proposal involved an interview, a format that Themerson distrusted just as much as biography, and for presumably similar reasons. This didn’t stop him parodying the technique in his fiction, usually in the form of a police interrogation. His objection, however, set in motion a dialogue that led Van Zuylen to re-propose turning Themerson’s own technique back on himself: interrogated by his own policeman, his own body of work placed under suspicion and scrutiny. Together, in dialogue, they take the format, the customary mode, and customize it. This, I conclude, is a prime case of aesthethical decency, too.

*