A Terminal Degree

2020

This was conducted via email over a couple of years for the eventual book One and many mirrors: perspectives on graphic design education (Occasional Press, 2020). As Luke describes in his introduction, it comes off the back of a PhD I had recently completed with the title “Work in Progress: Form as a Way of Thinking.” The submitted version is available here, but beware it is long (482 pages) and badly in need of editing; certain parts are ok but I definitely don't recommend wading through the whole thing.

Lead image: Dexter Sinister, Watch Scan 1200dpi, 2009.

*

This interview is an edited version of a sprawling email conversation conducted in 2015, shortly after Stuart Bertolotti-Bailey had completed a practice-based PhD at The University of Reading’s Department of Fine Art, UK. Bertolotti-Bailey initially studied graphic design at Reading in the early 1990s, and then became one of the first students to attend the Werkplaats Typografie in Arnhem, NL (1998–2000). Following this, he co-founded and edited twenty issues of the maverick design journal Dot Dot Dot, until 2010, when this publication was ended and replaced by the online-and-in-print Bulletins of The Serving Library. Bertolotti-Bailey has taught on and off at various design schools all over the world, and his essay “Towards a Critical Faculty” (2006/7), originally written for an academic workshop at the Parsons School of Design, NYC, was an influential reading for the project, (Graphic) Design School School, which spawned this book. Since the mid-2000s, the practice-based PhD has emerged as the new “terminal degree” for academically-minded artists and designers alike, and we were keen to hear about Bertolotti-Bailey’s experiences engaging at this level of study.

...

L: I’m interested in the institutionalisation of design practice, and what we might call “research,” because I’ve been a (sometimes sceptical) participant in it myself. And now, for example, as a full-time teacher at a university, there is increasing pressure on me to enrol in a PhD. I know you’ve just completed a PhD, so maybe we could just start with the obvious: when did you start, and what were your motivations to do something like this?

S: Basically, I was invited to do it. A doctorate is not something I’d ever considered before. I had, and still have, no academic ambitions that would require a formal qualification such as this—which isn’t to say it mightn’t be useful in some future situation I haven’t yet anticipated. It came with a stipend, roughly the same as what I’d be paid to teach somewhere, and being paid to write seemed like a good idea after fifteen years or so without that having ever really happened.

That said, there were at least a couple of non-mercenary motivations too. At the point of being asked in 2011, I’d co-founded, -edited, and -published the journal Dot Dot Dot for a decade, and was about to embark on its successor, Bulletins of The Serving Library. Most of the writing I’d done over the years was published in Dot Dot Dot, in which case it never had to meet with any sort of third-person approval beyond immediate colleagues. On one hand this was a positive thing, in that it gave the journal its very particular idiosyncrasy and independence, but the lack of objective overview also allows and fosters obscurity and opacity without question. And so I was interested at this point in trying to write along the same lines, knowing it would have to be peer-approved, argued against and, in the process, ideally worked over into something more rigorous and answerable.

Secondly, for years with the journals, as well as my work with David Reinfurt as Dexter Sinister, we’d only ever responded to circumstances without any masterplan. Again, this was helpful and hugely responsible for sustaining the energy behind a lot of the work—working blind and attempting to register situations on the fly. But it felt like time to stop and reflect on what it was we thought we were doing in order to realise a more considered direction. We were anyway simultaneously taking stock of Dot Dot Dot and Dexter Sinister, and trying to shapeshift both into something new with the same sense of longer-term projection. This is what led to The Serving Library, an attempt to take several kinds of activity that had developed over the years—the printed journal, an online library, parallel collections of objects and books, and a pedagogical programme—and synthesise them under a single coherent umbrella institution. This involved tinkering the journal’s publishing mechanism into something more digital, and making its subject matter even more free-ranging than before. All to say that it was generally a period of reflection for us, and so assembling a concerted body of writing as a “practice-based” thesis seemed fitting.

There was also the fact that the school doing the asking happened to be where I’d studied as an undergraduate, the University of Reading, just west of London. Interestingly (for me), I was a student in Typography & Graphic Design (on a very *proper* course of the kind that’s since been felled by the corporatisation of education—PhDs and “research” being part of the general thrust, of course). The invitation, however, was from the Fine Art department next door. Apart from a significant number of literally romantic entanglements, there had never been much communication between the two departments, however obvious and productive such a connection would seem to be. And given that I’d ended up working in the grey area between these fields, it seemed appropriate to return to do this at the rival department, so to speak. It was almost entirely coincidental that the invitation came from the same place, and I intuited that this could usefully shape what I might do. Practice-based art PhDs were still a new enough entity to preclude any clear models, and this, too, seemed conducive to my, and our, way of working. At the time, I was very taken with a book by Umberto Eco from the early 1960s, The Open Work, which seemed to dovetail with a lot of what we’d been up to with the journals and Dexter Sinister. All I could propose at the time was to take Eco’s thinking as a kind of springboard, in order to consider how our work relates to his ideas, and perhaps in the process update those ideas some fifty years on. In particular, I was attracted by the title of one chapter from The Open Work called “Form as Social Commitment,” which seemed to promise an explanation of how our concerns might have relevance beyond the art and design coteries that Dot Dot Dot and Dexter Sinister tended to, and still tend to, operate within.

So this was how I started. I applied, forgot about it, then unexpectedly found I’d been accepted. I should add that, having been in Melbourne lately, there isn’t (yet) the same sense of inevitability that people in our field end up doing this as an extension of teaching or that it’s a good way to pay the rent in lieu of any more meaningful work. It’s in the post, though.

L: I’ve been slowly digging into your thesis and it’s interesting because it becomes difficult, if not impossible, to separate the doing of the PhD (the structure and process) from the content of the thesis (the “working ethos” you’re trying to articulate). Which is also probably exactly as it should be—that “self-reflexive oscillation” between form and content you describe in the thesis.

That said, though, in terms of those non-mercenary motivations, how has the structure and process of the PhD—the peer review, the arguing against, the working towards something more rigorous and answerable—how has that paid off? Has it worked out more or less how you thought it would? Or did you meet with unexpected shifts in your thinking or outcomes as a result of being enrolled? If we leave out the obviously very valuable financial support of the stipend, do you think your practice would’ve developed very differently over the last nine years if you hadn’t been doing the PhD? I ask this mainly because, from my perspective at least, those “immediate colleagues” you mention were already a group of very astute, critical thinkers/practitioners anyway.

S: The promise of peer review didn’t play out at all as I’d anticipated: both the department in general and my supervisors in particular were very casual about the whole thing. Whenever I was required to submit bits and pieces along the way, I’d generally receive broadly approving comments and a few suggestions for further reading, but very little beyond that. I think this was partly by design, in that they trusted me to find my own way and didn’t want to impose anything that might hinder that, and partly because the sorts of things I would send were so long and unwieldy that they could barely get through it all before we’d meet up to discuss things, so anything “official” always felt incomplete and pending. This wasn’t helped by the fact that I didn’t write it as a series of progressive chapters, where each completed part would logically feed the next. It was more like a tornado. I’m clearly not an academic writer in the normal sense, and fortunately the department was trying to get as far away from that as possible anyway. In this sense, it was a good match: right place, right time.

That’s not to say it was completely unsupervised. The main points of contention related to my use of very general terms like “aesthetic” without any proper recourse to their involved histories, though it always seemed clear to me that I was using such terms in their most obvious, prosaic senses, and was happy enough to declare as much in the text. That’s to say, contesting what “aesthetic” might mean wasn’t really part of my point, and a rudimentary definition along the lines of “the form by which an idea is communicated graphically or verbally” was adequate enough for my needs.

There’s a small section near the start of the thesis that briefly accounts for my use of the words “aesthetic,” “poetic,” “art” and “design.” The first two are anyway derived from Eco’s usage and so are straightforward enough to summarise from his writing, but it was actually very useful to grapple with the last two. I tried to force myself to describe what these terms meant to me right now, without referring to historical lineage or received wisdom. This brought into focus my own sense of the distinction, and why I tended to prefer to refer to a more general “work” rather than classify stuff as “art” or “design” per se. I realised, too, that Eco also referred to a general open “work,” rather than considering openness in view of a single domain.

The other thing I recall during those early drafts is my chief advisor expressing alarm at what he perceived as my slipping into propagating what he semi-seriously called “Christian values”—honesty, goodwill, authenticity, and so on. This made me duly self-conscious, and I set about trying to articulate such notions in more concrete terms, but it also made me realise that I was indeed out to advocate what are basically “humanist” values, and so reflect on what that word means relative to art and design nowadays. There’s a paragraph on the first page of the introduction that attempts a kind of deadpan definition of the summary idea I’m trying to articulate throughout, namely “form as a way of thinking.” This fragment will give you an idea of the nature and the point of deconstructing the vocabulary:

Now, if in their most general senses ‘“form’”means a lasting encounter between atoms that hold good together, and ‘thinking’ the process of relating two or more discrete ideas in order to yield new ones, then “form as a way of thinking” in its most skeletal and pedantic sense describes the process of manipulating sensory matter—whether verbal or graphic—by juxtaposing, connecting or configuring already existing ideas with a view to generating new ones. It is a fundamentally constructive, progressive process.

Strangely, I found myself reading loads of those little Oxford Short Guides to Philosophy on anything that might seem loosely relevant—Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Derrida, Heidegger, and so on. I think this was my version of the kind of crisis of confidence I suppose most people experience at the beginning of a doctorate, a response to the fear of having to start from scratch and suddenly read every book you were ever “supposed” to. But I did wonder why my impulse was to focus on philosophy. Then a friend said, “well, you ARE doing a philosophy degree ….” I’d never consciously registered that that’s what PhD stands for—Philosophy Doctorate! So, again, as absurdly obvious as it might seem now, this was a good lesson in paying attention, in really thinking things through, and in sharpening the reflex to account for every single word you’re using.

Following this early flailing about in philosophy, there was a big gap before I discovered what I should be doing, meaning the overall shape and form of the thesis. This was also a result of painfully realising I couldn’t write in what I understood to be a typically academic manner—that it just killed any of my interest in the subject. I squeezed out a semblance of a first chapter, more or less a summary of the aspects of Eco’s book that interested me, along with a synthesis of related ideas from a string of heavy hitters like Benjamin, Adorno, Badiou, Sontag and Latour—which was a version of the usual “literature review.” Then I wrote an equivalent chapter conceived of as a kind of parallel introduction, more or less a literature review of the past ten years of Dot Dot Dot, including fragments from all the parts that explicitly dealt with that “oscillation of form and content” you mentioned.

It dawned on me that the whole thing could be structured along these parallel lines, alternating between chapters of so-called “theory” and so-called “practice,” which I supposed might ideally demonstrate the blurring of the distinction between the two that I was hoping to convey. At the time, I also wrote a convoluted meta-intro about this, i.e., the thesis demonstrating its proposition, which my supervisor quickly told me to cut, as pretty much every practice-based PhD explicitly or implicitly claims as much—and that of course it’s far more efficient and convincing to demonstrate it than to “cleverly” (= tediously) point out that you’re demonstrating it. It took a while to get out of such snake-eating-its-own-tail thinking, which in a similarly spiralling way also happened to be what I was trying to get out of my system with the final, very self-reflexive issue of Dot Dot Dot.

This zigzagging practice-theory-practice-theory structure was the first time I had any sense of an overall shape, and from there everything got a bit easier.

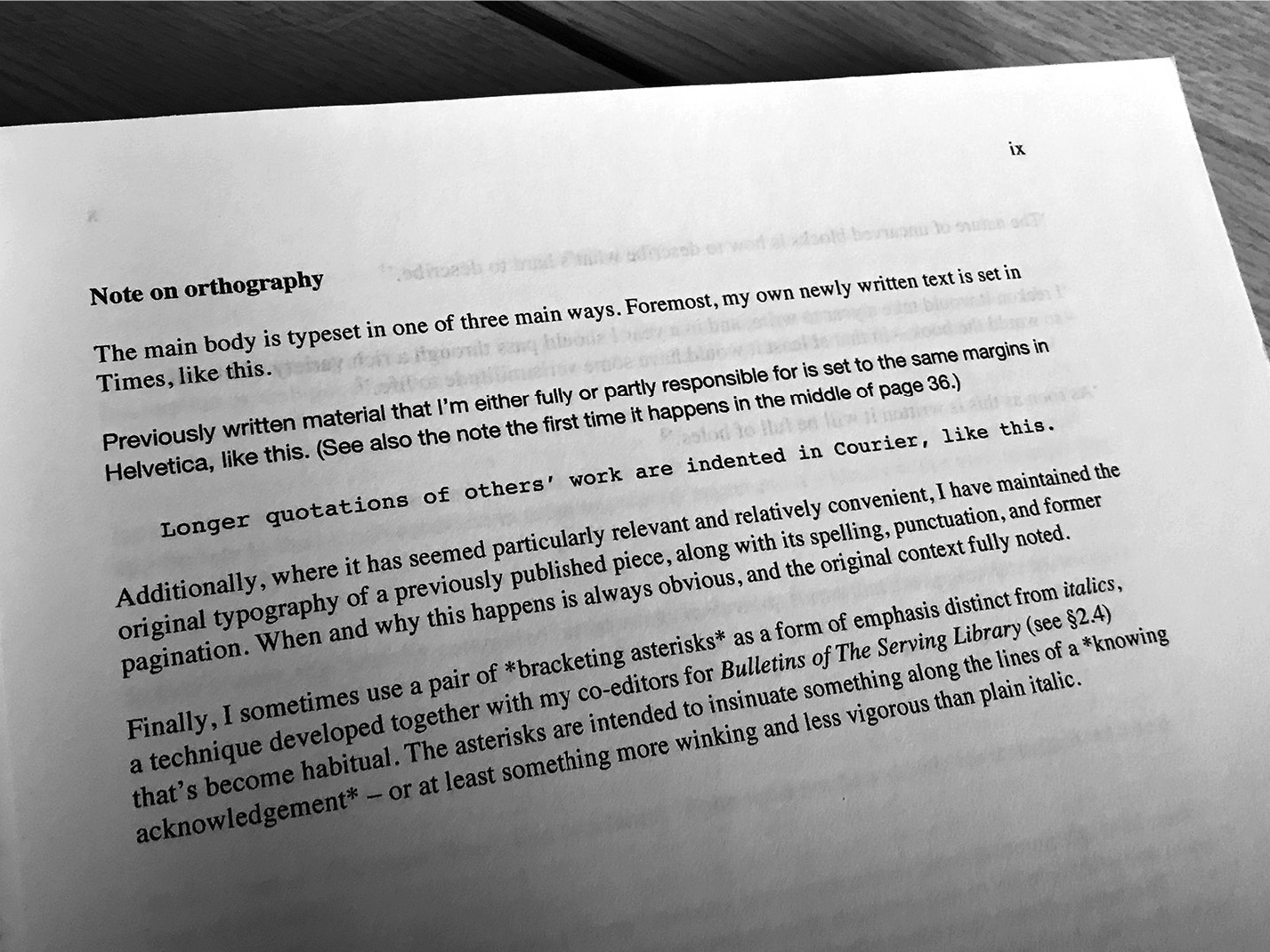

The next key thing I understood was that, as the Dexter Sinister projects I’d inevitably be writing about (inasmuch as the thesis was categorically practice-based) typically generated a lot of mannered writing, it would make a lot of sense to incorporate it into the whole. I began to think of any new text for the practice chapters as a kind of glue that could stick together the existing stuff, and that I might profitably maintain the original formatting in each case. As you might imagine, in our work, such formatting—typesetting, layout, distribution channel—is generally intended to say as much as the text itself. For this reason, such fragments would serve as illustrations as much as quotations. I saw, too, that I could achieve something similar with the theory chapters by incorporating certain auxiliary talks, interviews, letters and essays, and start writing for upcoming events with the PhD in view. If I squinted, I could just about conjure the ghostly outline of a last practice chapter based on some piece of work we hadn’t yet imagined, to be written in pronounced real time, which again was precisely one of the qualities of the way of working I was out to grasp. So that’s when it all coalesced as a single idea, though it was still a whole other story to actually do it.

I’m well aware that the procedures I’m describing here are fairly commonplace: the majority of people working on lengthy doctorates write bits and pieces for journals and conferences, etc., and use the occasions to shape and hone the work. Nevertheless, I did have the sense of having arrived at this point by trial and error, by working through it rather than having been told what to do, which I’m sure makes all the difference. Otherwise put, it felt inherent and organic rather than applied and artificial—which is once again the nature of the work the thesis attempts to account for.

L: I’ve talked to quite a few people who express concern that this thing, the practice-based PhD, could go either way. The formal processes and requirements of the institution could support, provoke or cajole you into developing your work in beneficial ways. But the weight of the institution, the structure, the formality, might equally crush a practice’s motivating spirit. There’s a lot of cynicism about PhD-level study in art and design, which comes from that sort of perspective.

S: I don’t think the PhD format crushed the sort of active spirit you mention, because eventually I came to treat it just as I, or we, would any other piece of work, whether an exhibition or essay or issue of the journal. Probably the main stumbling block in my case was that I’d become so used to working with David as Dexter Sinister, with all the benefits that brings in terms of security: strength in numbers, quality control, a certain propulsive hilarity in dealing with other people, and so on. Even if the thesis was fundamentally based on our work together, suddenly I was solely responsible for all the decisions, and that was hard.

L: I’m interested in the potential significance of this thesis being done at an art school rather than a design school. The “grey area” between art and graphic design is something your thesis addresses quite specifically, and yet you point out that there was no real practical or academic relationship between the two departments at the University of Reading. Do you think this PhD could have been done in a graphic design department? Or was the art school context necessary?

S: I don’t think I could have done the PhD in the Typography department at Reading (which is really a general Graphic Design department, just one with an enduring bias towards book design and the niceties of typesetting)—at least not in the way I ended up doing it. That’s not because it’s a design department per se, just that that particular department has more entrenched old-school academic expectations than its Fine Art neighbour. This is partly historically determined, and partly a consequence of the current staff. In this sense, the two departments conform to the stereotypes: the Typography department would have been far more strait-laced and uptight, where the Fine Art department was more speculative and searching.

To generalise wildly now, I often think that designers and design departments tend to get bogged down in details that aren’t as important as they assume, while artists and art departments are just as prone to airy abstraction and imagining their work communicates far more than it actually does. Part of my thesis argues for a merging of the best of both—towards a freer-thinking attempt to genuinely connect.

L: When you wrote that “I’m clearly not an academic writer in the normal sense, and fortunately the department was trying to get as far away from that as possible anyway,” can I ask you to describe where you think they (the department) were trying to get to instead? I’m interested to know more about what that might mean, to eschew the traditional academic narrative? I guess I ask because to some extent I think I yearn for some formality, to be forced, more or less, to submit my usually very woolly thinking to a strict framework of some kind—a scaffold. But then your comment about trying to write in a “typically academic manner” killing your interest in the subject also makes total sense to me.

S: As I said, rethinking how to approach an academic thesis outside the regular decorum seems part and parcel of the whole point of “practice-based” PhDs right now. But how might we account for the *extra* benefit of what we’re rather reductively calling “non-academic”?

Regarding both my own and the Reading Art Department’s view on practice-based academic work, my provisional answer is precisely that the *form* of the thing can add to (or multiply or supplement or reinforce) the “hard” meaning of the writing itself. Trouble is, this is already a bit of a knot, because to my mind such “extra-textual” qualities don’t only allude to the typography or layout, but to the writing too: the rhetoric, the style, the *way of writing.* Being exaggeratedly casual, for instance, admitting a bit of humour, or adopting and bending genre conventions. This is why I decided to include a number of fairly contrived conversations, letters to people, lectures and other “set pieces” that are pretty clearly outside the regular academic gamut.

In any case, for me this is the “extra” aspect that a typically freewheeling art or design temperament might bring to a typically uptight mode of academic inquiry. No one at Reading ever confirmed this directly; it was an unspoken assumption that became clearer to me through doing it. Of course, many people in more overtly academic fields—science, maths, philosophy, art history—might well be just as loose and inventive and by no means stick to what we imagine to be The Rules. The point is only that the practice-based model is an immediate license to think more speculatively from the outset, that conventional forms of inquiry are called into question as a matter of course, and this suits the particular talents and interests of those involved in the arts. None of which is to say that a more regular academicism is outdated or lacking; on the contrary, it has fairly obvious benefits (peer approval, etc.) in those other domains. All of this is surely tied up, too, with the fact that it’s easier to determine what science or maths are, as compared to art and design.

I think there were two main academic conventions that troubled me, that made me uncomfortable to a degree that outstripped any positive sense of having to answer to a relatively strict framework, which I looked forward to in the abstract as much as you. The first was the obligation to synthesise others’ writing. I became very self-conscious about this, perhaps because my impulse was to look outside my own founding domain of design to bits and pieces of philosophy, aesthetic theory and sociology—areas in which I have no grounding whatsoever. Although all the stuff I wanted to incorporate was absolutely helpful, to stick it all together formally felt like: “In 1960 person X said this, two decades later person Y said more or less the same thing, and recently person Z has written something similar, which is more or less what I want to say too.” It felt tedious to me—as if I might as well just give anyone a list of references and let them do the patchwork themselves. This was less the case when I forced myself to paraphrase rather than simply quote, but still. I think there are people who can do this sort of thing and manage to conjure something greater than the sum of parts, but for me it felt like it was just the parts. Spare parts. Over time, I realised that such synthesis is something David and I do all the time, but with the benefit of not immediately *appearing that way.*

So that was my first sticking point—the starchy quality of academic synthesis. The other was being obliged to write in a formal voice. I didn’t so much mind affected phrases like “What I want to do in this chapter is …,” or “As I argued in chapter four …,” as I could see easily enough that they were genuinely necessary to keep anyone oriented in such a sprawling piece of work, myself included. The problem was trying to write without contractions. After fifteen years of habitually having written “it’s” and “I’ll” and “he’d” in Dot Dot Dot and Bulletins, having to suddenly adopt “it is” or “I will” or “he would” felt out of character to such a degree that it outstripped any positive notion of answerability to the academic community. Simply put, I felt like a fraud, and more pointedly that I was doing something I wasn’t very good at with no discernible benefit.

On one hand, I can readily dismiss such informality as a contemporary tic, increasingly ubiquitous as written language tends more and more towards the relative laxity of speech, which equally permeates social media and serious journalism. On the other hand, I can also see that such nonchalance is analogous to the casual drift between fields that marks our work. In some obscure sense I can’t fully articulate, it seems appropriate to me that this blurring of borders requires an equivalent blurring of language. This has never been too conscious: we never sat down with a flip chart and said “Ok team, how are we going to embody our disciplinary looseness in language?” But as I think I say in that last theory chapter, it’s both what you do and the way you do it—or it can be.

L: I really liked what you wrote about working out ‘what these terms meant to me right now, without recourse to historical lineage or received wisdom’. Which is sort of anti-academic in the traditional sense, but, of course, entirely useful in terms of locating a more practical resonance between language and practice. Anyway, that comment actually reminded me of something you’d written before—that funny sort of misappropriation of “Design Thinking” in “Towards a Critical Faculty.”[1] I know one of the people you were supposed to be working with/for at the Academic Project Office at Parsons, and I know that when they used the term ‘Design Thinking’, they would have been using it in the sense that it has become widely known and propagated by the likes of Richard Buchanan and IDEO. However, you completely ignored that usage and went after your own sense of the term, via an altogether different historical lineage and a sense of received wisdom.

S: This brings to mind a radio conversation between Michael Silverblatt and David Foster Wallace on the NPR show “Bookworm” that influenced me a great deal. Silverblatt introduces Wallace’s essay collection Consider the Lobster and leads into his opening question by suggesting that whatever topic Wallace has been commissioned to write about—an article on conservative American talk radio, for instance—he’ll generally spend a good bit of time upfront debunking received wisdom on and around the subject. He tries to lay bare the mechanics of what’s *actually* going on, which are frequently contrary to the terms in which the subject is discussed by the mainstream media. This return-to-zero perspective, a kind of rebooting of the subject, makes apparent how much we’re unconsciously swayed by the ways in which things are reported—even, or maybe especially, stuff we might not spend a lot of time thinking about. Wallace observes, for instance, that the standard liberal response to conservative talk radio is to be outraged by its right-wing sloganeering and political provocations, when its main motivation is not politics at all, but entertainment—and as long as its critics address it on political terms, they’re missing its point, hence their counter-arguments miss their mark.

So this applies to my personal rebooting of “Art” and “Design,” and of “Design Thinking,” too, in that earlier Parsons essay you mention—trying to think about those terms *on your own terms* to avoid contamination by consensus opinion. I think having the kind of time and space necessary to really think for yourself at this level of detail is one of the real luxuries of undertaking an extended thesis. Even if you end up back where you started and agree with the received wisdom, your work thereafter ends up far more nuanced and convincing for having put yourself through the mangle.

L: I brought up Design Thinking here because I’ve come up against it a bit in the last few years at different academic institutions, most recently here at the University of Canterbury, where they wanted to set up a d.school following the Stanford model. Many things bugged me about it, but one broader issue I had was with the way Design Thinking was being portrayed: a clear emphasis or prioritisation of the thinking over the doing. The “dematerialisation of design” is, I guess, another way of putting it. It also seems to come packaged with euphemisms about design for social good, but only where there is money to be made. And, indeed, there was a sizeable corporate interest backing its establishment as a programme at our university. There are two points here that I’d like to explore: graphic design as a practice of form-giving, specifically, and the social value in that—both of which are critical components of your thesis. I’ve just read your “Chapter 9: Grey Area,” and through it are statements like this:

Rather than the way things work, Graphic Design is still largely (popularly) perceived as referring to the way things look.

The danger is that you read the form as though it sprang fully formed from the designer’s mind, in which case you tend to read it as an exercise in style, as formalism …

… usually another euphemism for formalism …

Graphic design then becomes simply—and boringly—an exercise in formalism.

It might sound naive and maybe I’m misreading you a bit, but I wanted to ask about this scepticism regarding formalism. I mean, I know we’re not supposed to make or read things superficially, but, more and more, I’m wondering why not? Why can we have a purely visceral engagement with, say, music, but not with graphic design? I listened to a Brian Eno talk recently,[2] in which he mentioned a scientist who claimed that one of the great questions of modern science could be “Why do we like music?” In this same talk, Eno outlined his belief that art or culture, which he sees as one and the same, is simply “everything we don’t have to do.” The “everything” he then talks about is “styling.” The implication here is that there is very much more to these seemingly superficial activities than we might presume.

This leads me to the question of social value. At the very beginning of your Chapter 9, you write: “the channels for a socially-oriented graphic design practice have been largely eradicated by an all-pervasive corporate sensibility that prioritises profit over culture—and hence bureaucratic concerns over aesthetic ones.” This sounds about right to me, but I know a lot of people would argue that this bureaucratisation of design—you mention “focus groups, marketing, and public relations departments,” and might we add Design Thinking to that list?—has been for the social good, for the benefit of a perceived audience, a user, or a public. And, that “aesthetics” are just far too subjective and superficial to be worth any real interest or concern. This is what I come up against regularly, anyway. So, if design is supposed to be primarily concerned with a broader sense of problem solving and with the improvement of society in general, what role does aesthetics have to play? And is there not a contradiction here, in the sense that you’re concerned about graphic design being perceived as an exercise in formalism, but then lamenting that bureaucratic concerns have overtaken aesthetic ones? Am I misreading your use of the concepts of formalism and aesthetics here?

S: Part of the problem is that these things are so general, the subject so expansive, and I tend to object to the term “design” being bandied about without qualification, given that it can be used in so many senses. I think anyone dealing with the subject should be obliged to state precisely what they take the word to mean, otherwise it fosters confusion. This is why I wrote, in the “Towards a Critical Faculty” piece for Parsons, that, for me, “Design Thinking” is a tautology: to my mind, designing in its most general sense is thinking, not a way of thinking. In a casually underinformed way—partly because I can’t bear the slightly creepy Design Thinking rhetoric—the IDEO-ish approach reads to me like a lot of hot air and self-justification for charging a lot of consultancy money for something that’s actually pretty unremarkable, a means of making little more than common sense seem professionally particular. From what I gather, “Design Thinking” supposedly means thinking outside the usual ways of doing things, with a bias towards “iterating” different possible solutions and letting those iterations lead you to places you may not have readily conceived otherwise. Er: *thinking.*

As my Wallace anecdote suggests, I support this. (Who wouldn’t?) It’s the glorification of the idea that bothers me. This is why, unfashionable as overkill and deification have made him at this point, Wallace was and still is such a touchstone for me: his resolve to get to grips with the root level of whatever subject he was dealing with, without making a big deal about doing so. The fact that he was so free-ranging in subject matter makes him all the more exceptional as a model.

Anyway, if we’re talking about formal aspects of graphic design as synonymous with “style” in the sense of “formalism”, or form for form’s sake, my sense is that style *in itself* no longer has the sort of meaningful power it had in the past. This is close to saying that I think “everything’s been done,” though I hesitate at how reactionary that sounds. What I mean is, I can appreciate how throughout the relatively short history of graphic design there have been many moments when the surface appearance of, say, political protest posters, or punk record sleeves, or a classically designed book, or an Isotype chart, have carried a certain quality in themselves (i.e., have carried meaning distinct from, if ideally as a reinforcement of, the raw content, the base material to be manipulated). These days, style inevitably refers to something already done. Perhaps the last of such vanguard styles occurred in the 1990s. I’m thinking of work by designers such as Tomato or Emigre or Jonathan Barnbrook or David Carson, a breed of conspicuously “experimental’” was often its stated aim. I had and still have no particular affinity with or appreciation for that stuff, but I can see readily enough that style was the primary point, towards what aesthetic philosophers call “affect.” A favourite book of mine, Michael Bracewell’s The Nineties, has a subtitle that sums this up beautifully: When Surface was Depth. So I’m saying that, since the 1990s, surface no longer has such depth.

I’m sceptical, then, about what we’re calling formalism in graphic design today communicating very much as an end in itself. I’m less sceptical of this idea in the realm of fine art, which is a whole different matter with a different set of attendant problems. But I’m alluding specifically to the idea of form treated as something distinct from content, something that can be “applied to” the raw materials of text and image. I know well enough you can’t not have style. That’s to say, pedantically conceived, everything has a style, “non-style” is a style, etc., in which case, perhaps “stylish” is a better word. But in the realm of graphic design, which I define in the PhD as “the articulation of text and image, ideally according to meaning,” stylish work no longer has much purchase. Certainly, I find the idea of teaching graphic design stylishness to students fairly pointless, not least because what tends to happen out in the world of work is that someone says, “we want this (menu, T-shirt, billboard, web ad, homepage) to look something like that (fancy, minimal, distressed, baroque, ironic).” To become proficient in this, you don’t need to be taught how to think, you just need to look around and scavenge. It’s possible, it’s fine, it amounts to a certain “vocational” education in that it makes you “employable”—but it doesn’t interest me. More dramatically put, it’s complicit with our contemporary condition: homogenisation, blandness, monoculture, etc. I think in education and elsewhere, it’s important to resist that and to open up other, more thoughtful and less predictable avenues.

So, for instance, I do think that there’s a sense in which form can be appropriate to or *at one with* the internal meaning of its material in a way that’s fundamentally different to the sense in which “minimalism” might be considered appropriate to, say, Nike’s Fall 2015 marketing campaign. And this, I suspect, is where you and I align in thinking that form-giving is the sort of thing that can be usefully taught: a sensitivity to meaning and how to translate that meaning via other materials, formats and channels. This is very much a *social activity,* though fundamentally different from one that’s only involved in trying to sell things by making superficial differences to more or less the same products or institutions.

Following Eno, you wonder why there should necessarily be a fundamental difference between the way we think about graphic design and music? In view of this question, what I’m saying, I think, is that graphic design no longer functions in an “abstract” sense equivalent to music—at least in the way Eno conceives of it. Then again, my suggestion is not a million miles away from the way certain commentators argue that pop music has arrived at or is approaching a terminal point—not as some reactionary, middle-aged complaint, just as a kind of hard fact about the inevitable lifespan of a cultural phenomenon, like a used-up mineral resource. And so it seems endlessly more interesting and necessary to me to engage with graphic design not as a form of formalism but as a form of articulation. Trouble is, this requires material worth articulating. And, as far as I can see, the sheer number of people who consider themselves graphic designers combined with the sheer scarcity of third-party work worth working on has led to a state of confusion, hence the blurring of roles and activities that doesn’t make things any clearer but has forged a lot of escape routes.

I challenge you to give me any counter-examples to what I’m saying about contemporary formalism in graphic design, and I’ll be happy enough to stand corrected. It’s maybe worth adding that I don’t see new formalisms in graphic design—in the sense we’ve been using—happening in the realm of digital media. I think this is partly because the interfaces are so limited in scale and capacity, even though we may instinctively suppose that they’re far more flexible and generative than print, and partly because the software monopolies always already short-circuit the potential of these new formats. Think, too, how difficult it is to ensure that anything out of the ordinary on a website will function properly across diverse platforms, browsers, and so on.

As such, I think computer programming ought to be a foundational component of any design school today, simply in order to avoid immediately working within industry defaults. The better websites and the better forms of digital publishing today surely have little to do with graphic design style, and more to do with how intuitive they are to use, and how navigable they are. Ultimately, I suspect that your university’s penchant for immaterial Design Thinking and your own convictions about, um, “material” graphic designing probably aren’t that far apart; it’s just the methodology and the rhetoric that are at odds. You’re all for teaching people how to think *by making things*, in which they have to respond to limitations and contingencies and materials and make informed choices towards particular ends. And I’m sure that aligns with the sorts of skills the DT-ers want to foster via more conceptual means. My concern is that teaching Design Thinking remains uselessly vague until it’s actually applied, that it requires an object to work in order to face the generally messy and unpredictable realities of a given situation. When the Parsons crew were initially explaining Design Thinking to me and going on about “iterating,” I thought, well, if I’m going to drive up to San Francisco from LA this weekend, don’t I “iterate”—in my mind, without a pen and paper, or even Google maps—which of the three likely routes I should take according to my knowledge of their various benefits, then choose one accordingly (and possibly get stuck in traffic for reasons beyond my control). Is this Design Thinking? I think it’s common sense.

Moreover, I don’t think that your methods being more material means they’re any less “social.” For me, the rational thinking that any mode of teaching might encourage can equally be directed towards social or antisocial (capitalistic?) ends. Like you, I don’t see the inherent link between Design Thinking and social values. As you imply, too, I suspect it’s more frequently directed towards economic ones.

One last thing here. A couple of years ago, I taught a seminar class to graduate graphic design students, and at some point asked them each to “bring in” four or five websites they appreciated *for the design*—though I was careful to add that by this I meant in view of the way they work, rather than their stylish style. To my surprise, almost all of them pointed to the four or five most ubiquitous, high-traffic sites, often search engines, including Wikipedia, Craigslist, Reddit, even Google. It made me realise that such sites are barely graphic-designed in that overtly stylish sense, but extremely well designed in terms of user-friendliness, often in very smart, subtle, sophisticated and what seem satisfyingly inevitable ways. I thought, too, that in some sense this must be because they’re designed, or at least refined, by large aggregates of people—including the users themselves, whether directly or indirectly. Moreover, being digital, they can be amended and updated any time in a way that’s not possible with the relative fixity of print. For me, this is where the really interesting work is happening in graphic design—far more interesting, at least, than whatever might be the equivalent of the formalisms of the 1990s. It’s work that’s more concerned with the way things work than with the way things look (one doesn’t rule out the other, of course; it’s just a matter of priorities). As for the more “musical” ways of working with form in Eno’s sense: I think that’s art. And graphic design usually makes for terrible art, which is to say, not art at all.

L: This reminds me that in “Towards a Critical Faculty,” you stated that before we thought about how to teach we needed to know exactly what we were teaching. And so, given that your PhD was a “movement towards the heart of the matter,” as you say, I was interested to ask you about that. Can you tell me about your experiences of teaching, and about how your work towards the PhD might have affected that?

S: My first teaching experiences were in the graphic design department at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. Under the direction of Linda van Deursen in particular, it was regarded as a very ‘conceptual’ course, which meant something closer to an art practice, less concerned with teaching what we might think of as traditional design skills. Projects typically involved coming up with content as much as communicating it—or at least both were entangled in ways I didn’t always find productive. I’d had such an opposite education at the University of Reading, where the whole class would typically be given the same raw material and a very specific brief in view of turning it into, say, a magazine, a book, a poster, a signage system, a timetable, or a webpage. (This was the early 1990s, so they were the very early days of the internet and of ideas of what digital publishing could mean.) What I noticed then, and which is far more common now, is that if you require students to fold their own interests into the brief—to be responsible for the content—they often spend at least half the project’s run trying to work out what they’re interested in, and by the time they’d sorted that out there was hardly any time to critique and refine it in view of anyone else receiving it. In other words, there was no time to sketch, to “iterate,” with actual material towards particular ends. This way of working presupposes that students are invested in subjects enough to bring decent material to the table, but I often felt that this simply wasn’t the case, that they didn’t care enough about what they were working with, and so came up with fake, temporary interests for the sake of the project, which is often what made the work weak and insubstantial. Their learning would have been far better served by having material carefully considered by a teacher and imposed after all. There was an air of personal therapy about the whole thing that I didn’t like either. In a way, it didn’t matter much, as I usually tried to do the opposite, imposing a bit of hardcore Reading-like specificity on the class. And this usually worked, because they were hungry for something else. It was probably a relief to them to relinquish responsibility for the content, but there were also those who just couldn’t understand the lack of personal investment. In any case, all this instigated my minor crisis of not-knowing-what-I-was-teaching- to-what-end. I suppose it’s quite normal.

However, when I then moved to the US and started doing a few small things with equivalent schools there, I realised how relatively sophisticated those Rietveld students were. This is a massive generalisation, but to my mind the undergraduates at the Rietveld ended up far more capable and interesting than their graduate equivalents in the US. So it made me reconsider things, and I could eventually accept that the so-called “conceptual” approach at the Rietveld did actually make them better and freer thinkers, more self-critical and questioning, less bound to conventions and ultimately more engaged. Still, I couldn’t perceive how they might go about working on anything that would promise the same level of engagement after school and simultaneously pay the rent. That’s to say, I couldn’t see the vocational benefit of a well-rounded humanities education. With the benefit of hindsight, I now think that was more a lack of imagination on my part, and that they’ll figure it out—quite possibly in areas that have nothing to do with their base subject.

I’ve come around to the idea that helping people to think critically is more important than helping people to be employable. This is a blindingly obvious idea, if a very unpopular one in some quarters. It certainly goes against the whole shift of education towards the quantitative, corporate–bureaucratic model. So I eventually worked out I was more comfortable with the idea of helping people develop those “critical faculties” than teaching them to be graphic designers in the old “hard skills” sense, particularly as desktop publishing was ever more prevalent and so “professional graphic design” was increasingly unnecessary, or at least deemed unimportant by whoever the equivalent of the previous generation of employers might have been. Today it would seem to me enough for anyone who wants to work as a graphic designer in a, let’s say, “standard” sense to simply learn Creative Suite and be aware of what’s around them, because, as I’ve said, most regular work in typical design studios involves, more or less, the copying of things that already exist. Meanwhile, the more thoughtful types who find that sort of thing completely tedious forge their own working contexts in the same spirit as those Rietveld projects. It’s not straightforward, it takes time to plot a course, but I think this is the path of those who have ended up assuming the wider roles that graphic design is now associated with—writing, publishing, selling, distributing, and so on.

As for how the PhD connects with this: I think the main thing is that the chapter called “Grey Area” tries to account for what this supposedly “thoughtful” wing of graphic design is up to, exactly—the sort of work that has no obvious commercial application, that’s more “philosophical,” which doesn’t fulfill an obvious brief, and which is largely if not exclusively self-generated. For instance, we publish essays on many different subjects through The Serving Library, but we’re equally interested in publishing as a subject itself—and so the *ways* in which we channel things tries to draw attention to certain aspects of contemporary publishing in forms other than writing. I end up concluding that, like many artworks, they’re “tools for thinking”—or, better, “tools for psychic survival,” a favourite phrase of mine, though I can never remember who said it. But ideally these grey area equivalents are more oriented towards a public audience than I think a lot of “straight” art is: directed outward, more generous, more cosmopolitan. And I propose, too, that the benefit of this art/design crossover at best is to bring the desire and talent for communication to bear on speculative, philosophical ideas in an age in which much contemporary art is emphatically uncommunicative, hermetic and, I think, spectacularly delusional about the extent to which it actually puts its ideas across.

L: One more thing: your comment about the lack of “material worth articulating” and how that has “generated a lot of escape routes”—are these escape routes the same ones you talk about in your final theory chapter under the heading “Orphaned Interests”? You’re quite critical of the surge in independent art and design publishing and the attendant proliferation of book fairs. I don’t necessarily disagree with your sentiments here, but am keen to ask you to elaborate. In particular, this part interested me:

… the uncommercial counterpart is generally drawn from someone’s personal, niche interests with no real profit motive and no urgent need for an audience either. Such productions inevitably foster a certain amount of community and goodwill, and it would be churlish to see this as negative; but in being so self-serving they’re not really “socially oriented” in that former sense either.

S: I think it relates to that trend of setting “personal” projects I mentioned, where students are suddenly required to supply the content as well as the form. It’s surely no coincidence that this happened around the advent and proliferation of social media: everyone’s-a-publisher-artist-designer-whatever. In the PhD, I quote a teacher of mine who wrote quite plainly that progressive design—meaningful work that isn’t only concerned with generating the superfluous differences that drive capitalism—can only take root as one facet of a general atmosphere and programme of social construction. It’s hard to find any semblance of such a spirit nowadays, at least compared to, say, after the Second World War in the UK, which is the era in which that Reading University course I did was incubated, and that attitude was still mostly intact while I was there. In other words, graphic design there was absolutely considered a positivist project, with the idea that texts and images could be communicated in more or less correct ways, in order to share ideas publicly, towards making the world a better place: more navigable, more cultured. Notably, “information design” was a key component of the course.

But, in a contemporary context, where that broader sense of social constructivism seems shut down, overtaken by such things as the ironically antisocial tendencies of social media and iProducts, there are individuals and groups sensitive to all the ersatz, infantilism and disconnection. They quite possibly ended up in areas like graphic design in the first place thanks to an interest in (and/or talent for) sharing ideas. These are the “orphaned interests” I’m on about, the ones who step sideways into the broader roles attached to graphic design like writing, publishing, selling and distributing: an ever-increasing pool of design graduates dealing with an ever-diminishing supply of worthwhile work, who end up making work for themselves, who take the “escape routes.”

On one hand, I see this as a positive thing, but it also makes me uncomfortable, as I’m still rooted in the humanist idea that graphic design is fundamentally about multiplying ideas for the common good—to generate thoughtful, meaningful, critical culture. This discomfort is due to seeing the sheer quantity of the stuff being produced (specifically the small, often exquisitely designed publications and other printed matter about fairly esoteric subject matter that flood the book fairs) and suspecting that the process of making it is the real point, as opposed to anyone else reading or looking at it. There’s a horrible sense of this corner of culture being totally *unbalanced,* out of whack, that the idea of multiplying matter in the hundreds or thousands is being applied to stuff that really only requires one or ten for family and friends, as proof that something happened rather than as a vessel for transmitting ideas. Hence it all arrives with some pervasive sense of waste, like a food mountain—a depressing surplus. To borrow a term that always affected me as a student, this sort of work has no sense of *requiredness*—no standards, quality control or reason for existence beyond a bunch of people occupying their time. That’s what bothers me: the mass solipsism it implies.

•

Notes:

1. Stuart Bailey, Towards a Critical Faculty (Only an Attitude of Orientation) From the Toolbox of a Serving Library (New York: Dexter Sinister, 2015), 4.

2. Brian Eno, “2015 Brian Eno,” BBC Music John Peel Lecture, BBC Radio 6 Music, 27 September 2015.