Poetic License

2025

The lengthy preface here explains my thinking behind this “time translation” of Edgar Allen Poe’s 1846 essay “The Philosophy of Composition,” so no need for any further note here other than to say thanks to the various students who commented on the translation when we discussed it during classes, and to James Langdon and David Reinfurt who also both responded to it along the way.

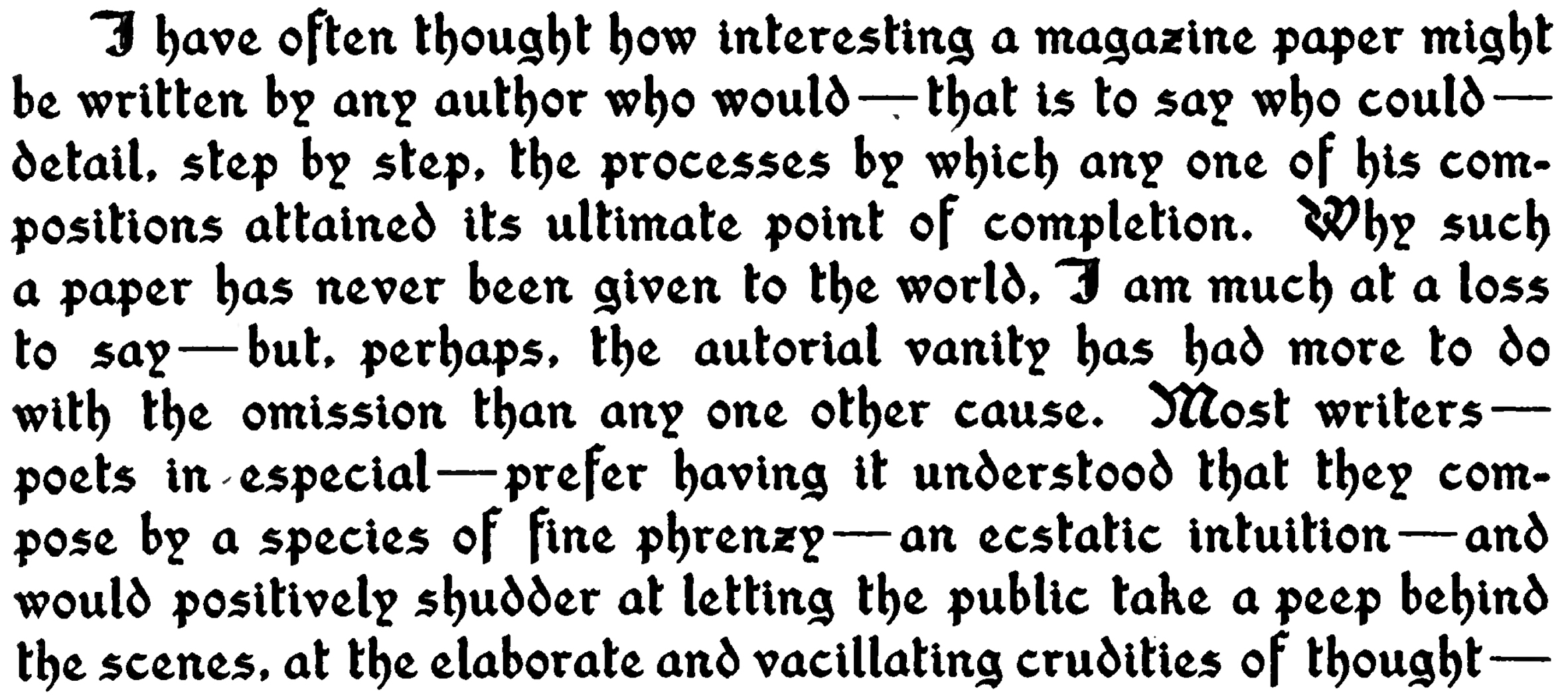

Lead image: A fragment from Poe’s original text as published in The Raven and The Philosophy of Composition (New York: Paul Elder and Company, 1907) – a complete scan of which is available here.

*

“The Philosophy of Composition” is in fact an account of how he wrote The Raven, which he insists was effectively constructed in reverse with a distinctly mathematical diligence – rather than from within a state of “ecstatic phrenzy” that he says most poets back then claimed to be their natural state of creation. Appropriately enough for the inventor of detective stories, it is written in the manner of a police procedural, tracing step by step how the poem came about. Part of what I like about this exercise is how its working principles can be so easily transposed to other fields. It simply, or complexly, demonstrates how the application of reason can generate an outcome – how to design (verb) a design (noun). I face an equivalent “problem” when setting out to work on, say, a catalogue for an artist, or signage for a building, or a website for a sound archive, or social media for a bar. I gather the various demands, parameters, preconceptions, and other “clues,” then deduce how best to corral them all into a convincing result – whatever “convincing” might mean in the given context.

Poe is of course writing about literary rather than applied art, and as such his premise is more subjective than objective, but it’s no big leap to carry the way of working, the same spirit, over into a different domain. One high-profile proof of this is that the French composer Maurice Ravel based his seminal Boléro (1930) very precisely on the essay’s instruction. Generally speaking, Poe’s work was far more well-received in France than his native country thanks to the gilded appreciation of such as Mallarmé (who translated The Raven), Baudelaire, and Valéry. Ravel praised the essay as teaching him “that true art is a perfect balance between intellect and emotion,” and – mindful of Poe prioritizing structure over substance – once described the Boléro as “orchestral tissue without music.”

Dismantling ingrained preconceptions is always good for anyone’s cultural wellbeing, and one of the invigorating aspects of the “Philosophy” for me is simply that it argues for the contrary of how I would usually begin a piece of work. Namely, Poe advises to start at the end with the desired effect first in view, and then reverse-engineer how to get there. Great. But it was the essay’s fifth paragraph that really made me sit up and realise I was reading something extraordinary. In a sleight-of-hand that seems way ahead of its time in terms of self-awareness – and irony – Poe writes that he had himself always wanted to read an author’s explanation of how they wrote a particular composition, but, in lieu of no-one having so far attempted such a thing, will have to do so himself … and then proceeds to do it.

The more prominent reason the text speaks to me, however, is that it is decidedly difficult to tell how serious Poe is being. The essay reiterates several literary theories concerning the nature of beauty and “unity of purpose” that he laid out elsewhere, most prominently in a far less slippery piece called “The Poetic Principle.” But the logical reasoning he shares in the “Philosophy” are asserted so definitively as to make the sensible reader squint and wonder how much mischief is at work – presumably at the expense of his more po-faced detractors, or maybe po-faced people in general. Indeed, many commentators have flatly dismissed it as a hoax.

This is understandable if you consider, for instance, a section concerning a poem’s ideal length. Poe asserts that an essential – not desirable, essential – quality of any poem is that it is designed to be read in one sitting, in order to ensure that the affairs of the world don’t intervene and disrupt its necessary unity. And he has no hesitation in declaring that the maximum is 100 lines – though later acknowledges even he couldn’t meet such exacting standards given that The Raven came in at 108. Or, on contemplating the single-word refrain he divines to be the necessary pivot on which the poem must turn, after declaring that the most “sonorous” vowel in the English language is o and the most “producible” consonant r, he continues: “In such a search it would have been impossible to overlook the word ‘nevermore’” – and lo and behold, “it was the very first word that suggested itself to me.” A foregone conclusion, then!

The important thing to note about this ambiguity – is he for real? – is that it doesn’t matter. Whether Poe really conceived The Raven in the manner he describes is irrelevant; the point is, he could have done, or somebody else could, and this is precisely what gives the piece the breath of life: Poe surely had a great old time writing it, and the energy of absorption is palpable. You can almost picture him cackling away on first having thought up the idea for the essay (starting at the end), then having the wherewithal to construct it in a convincing way. This is ultimately the “Philosophy”’s most enduring lesson – how to follow the unwavering arrow of a good idea through to its target conclusion.

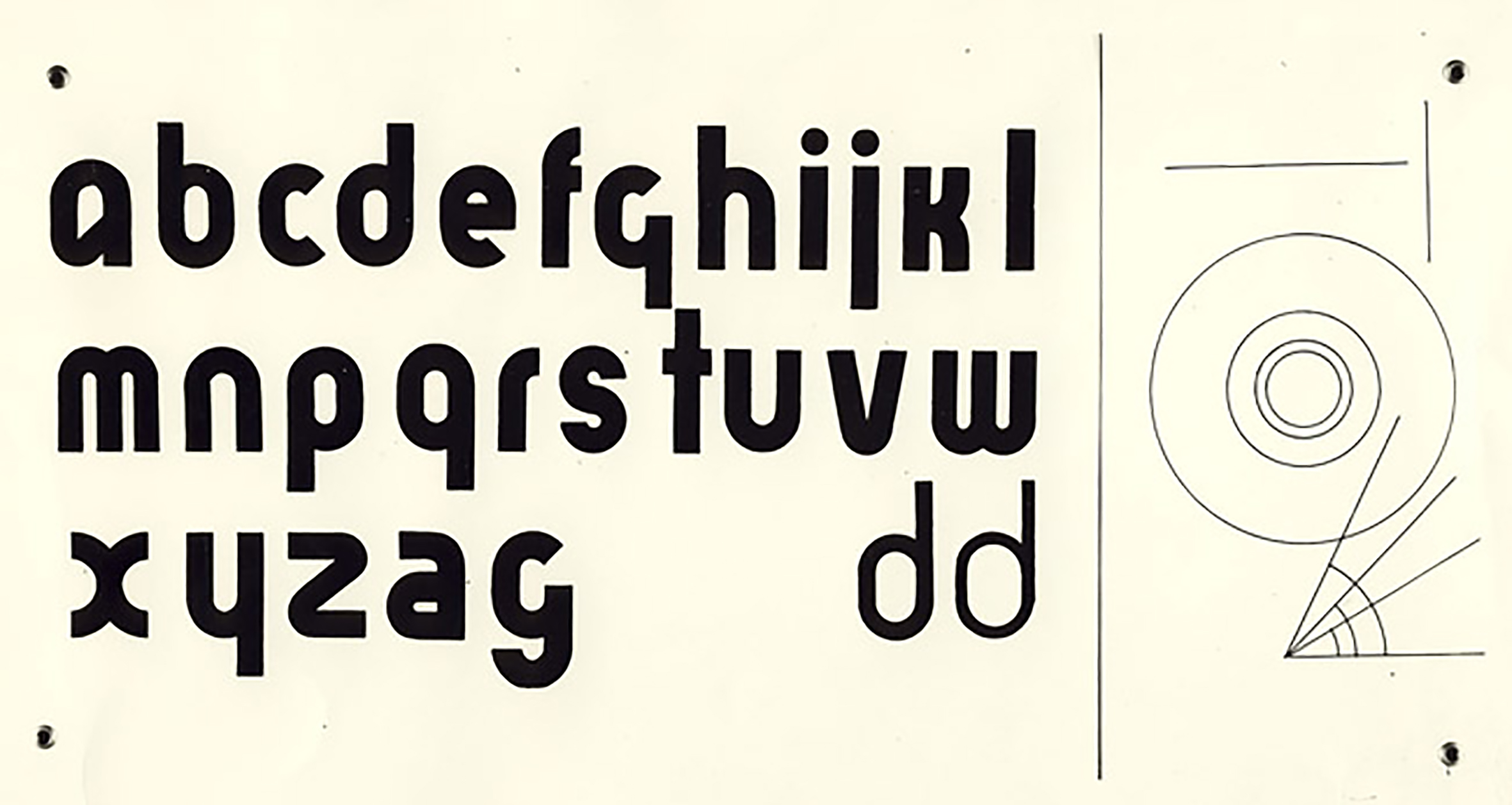

This latter characteristic reminds me of a couple of typographic siblings. The first is a small postcard-sized panel by the Austrian polymath Herbert Bayer demonstrating his 1925 Universal Alphabet, a pared-down sans-serif comprised exclusively of lower-case characters. Bayer adapted the basic glyphs for typewriter and handwriting, experimented with phonetic alternatives, and proposed a wide family of variants. Within the confines of the card, alongside the basic character set of its condensed bold version and allusion to other weights, he has also abstracted the tools used to draw it: ruler, T-square, set-square, compass, and protractor. In this way, the drawing effectively captions itself, pointing to its point – that this is a project intrinsically concerned with a particular mode of construction.

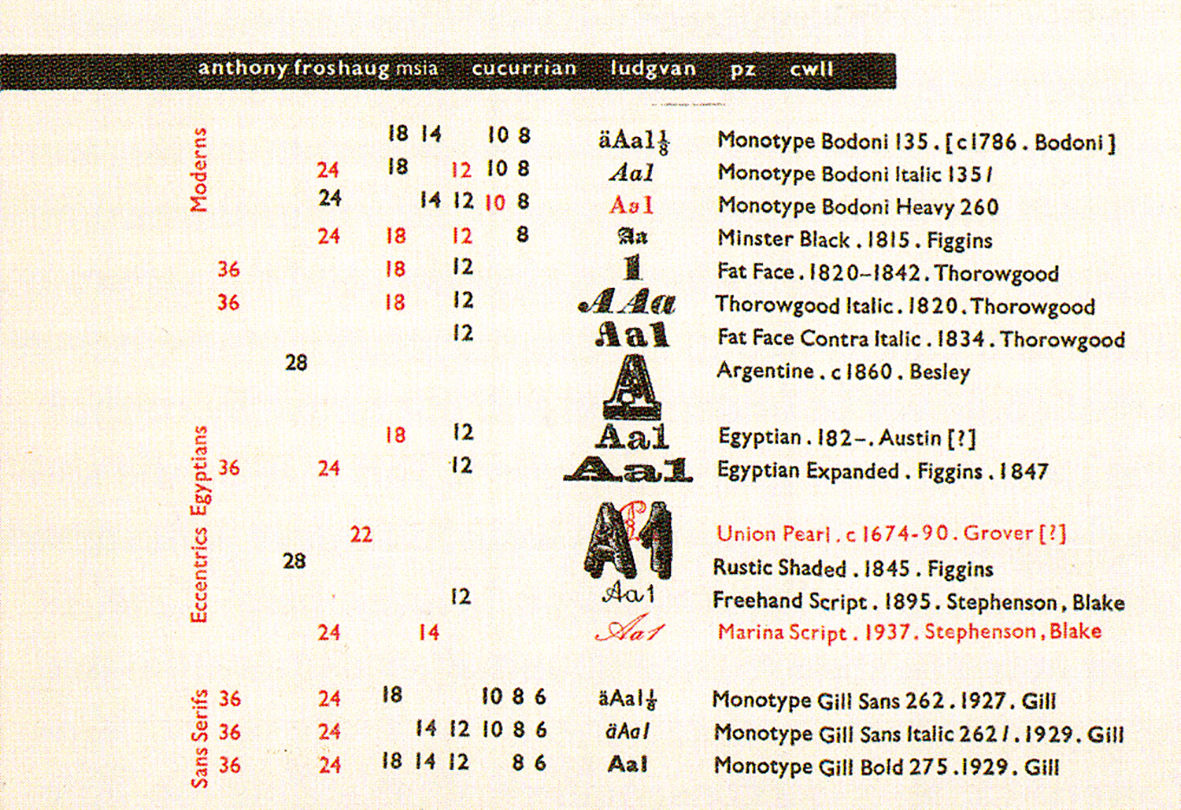

The other example I have in mind also happens to be a small card, this time made by the English typographer Anthony Froshaug in 1951, and even more impressive regarding the amount of intelligence that is squeezed into its 148 × 105 mm (A6) format. It also happens to be another sample chart – an inventory of metal type in Froshaug’ own workshop, printed to show the extent of what’s available and possible, a table of tools.

The various elements are clearly configured according to their relational meaning; arranged, that is, according reason immanent in the raw material, the information to be conveyed. Hierarchically, the types are grouped first according to historical style (the four categories set to read vertically up the left edge: Moderns, Egyptians, etc.), then, within these sets, listed roughly according to size from small to large, grouped in families (roman, italic, bold, etc.) and coloured black or red according to availability. The whole is organized around a central axis that proffers examples of each typeface (A’s, 1’s and, where available, fractions), with sizes-in-stock set in a matrix that runs off to the left and supplementary information (year designed, designer) to the right.

With Poe’s detective instinct in mind, then, it’s plain to see how the card’s subject matter (the material possibilities of a particular press) along with the its specific purpose (to set it out as clearly and quickly in as small a space as possible) have determined what we might consider is an authentic configuration – in the sense of having been articulated “true” to the intrinsic nature of the information. Or in Poe’s words, to “render it manifest that no one point in its composition is referrible either to accident or intuition – that the work proceeded, step by step, to its completion with the precision and rigid consequence of a mathematical problem.”

I have shared the essay – and some spluttering version of this introduction – with countless friends and students over the years, but was always a bit concerned that they might not get into it, might discard it, due to the somewhat dusty patina of Poe’s antebellum rhetoric. In other words, it might be perceived merely as a “historical text,” missing out on its timeless sensibility. And so I decided to upcycle Poe’s “Philosophy,” time-translating the text with a voice more native to 2025 than 1846 and hopefully not doing too much violence to it along the way. The original is naturally easy enough to find online, so anyone so inclined could compare, for example, Poe’s “Nothing is more clear than that every plot, worth the name, must be elaborated to its denouement before anything be attempted with the pen,” to my version: “It goes without saying that every plot worth the name must be thought through to its climax before anything be written down.” Given the impish nature of Poe’s character, which comes across in most biographical accounts as well as his work, I like to think he would have readily afforded me the Poe-tic license to perform the following operation on his text.

*

In a note I have here from Charles Dickens concerning an examination I once made about the mechanism of his novel Barnaby Rudge, he writes: “By the way, are you aware that Godwin wrote his Caleb Williams backwards? He first involved his hero in a web of difficulties, forming the second volume, and then, for the first, cast him about for some mode of accounting for what had been done.”

I find it hard to believe this was Godwin’s exact way of working, and actually what he acknowledges himself is not really what Dickens claims, but the author of Caleb Williams was too good an artist not to perceive the advantage gained from an at least somewhat similar process. It goes without saying that every plot worth its name must be thought through to its climax before anything is written down, because it is only with the final act constantly in view that can we give a plot its indispensable air of consequence, or causation, by making the incidents – and especially the tone at all points – support the development of the narrative.

There is a serious error, I think, in the usual way a story is constructed. Either history suggests a theme, or one is suggested by an incident of the day, or the author combines a series of striking events to form the basis of a narrative, and then proceeds to fill in the gaps with description, dialogue, or comment.

I, on the other hand, prefer to work the other way round – to begin by considering the work’s effect. Keeping originality at the forefront – for who in their right mind would relinquish such an obvious and easily attainable source of interest? – I start by asking myself: “Of the innumerable effects, or impressions, to which the heart, the intellect, or the soul is susceptible, which one will I select on this particular occasion?” Then, having chosen firstly an original and secondly a vivid effect, I move on to consider whether it can best be achieved by tone or incident; that is, through form or content – whether by peculiar form and ordinary content, or vice versa, or by the peculiarity of both form and content. This settled, I look about (or rather within) myself for combinations of tone and incident that shall best help me achieve my desired effect.

...

I have often thought how interesting it would be to read an article written by any author who would – indeed, who could – detail, step by step, the processes by which any one of their compositions reached its final state. I find it hard to understand why such an article has never been offered to the world, but probably authorial vanity has more to do with it than anything else. Most writers, especially poets, prefer people to imagine that they compose in a kind of inspired frenzy, an ecstatic intuition, and would shudder at the idea of letting the public take a peek behind the scenes at the elaborate and vacillating crudities of thought; at the true purposes seized only at the last moment; at the innumerable glimpses of ideas that arrived in an immature state; at the fully matured whims discarded in disrepair as unmanageable; at the cautious selections and rejections; at the painful erasures and interpolations – in other words, at the wheels and pinions, the scene-shifting equipment, the stepladders and trapdoors, the cock’s feathers, the red paint, and the black patches which, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, constitute the precarious mechanisms of the literary machine.

That said, I am well aware that we cannot assume an author is able to retrace the steps taken for the work to end up as it did. Generally speaking, more or less haphazard inclinations tend to be pursued and forgotten as part of the same perilous process.

Personally I have no sympathy with the reluctance of authors to recount their true operations, nor the least difficulty in recalling the progressive steps taken in my own work. And since my desire to read such a reconstruction is independent of any specific case, I consider it perfectly valid to show the modus operandi by which one of my own works was assembled. I will choose my poem The Raven for this purpose, simply because it is the most widely known of my ouvre. My goal is to demonstrate that nothing in its composition was the result of accident or intuition, but rather that the work proceeded step by step to its completion with the precision and rigid consequence of a mathematical problem.

Before doing so, we shall note the circumstance – or necessity – that originally gave rise to the poem. It was published almost simultaneously in a prominent weekly newspaper (The New-York Mirror) and a monthly periodical on politics, literature, art and science (The American Review). As such, my intention was to compose a poem that would suit at once both popular and critical tastes.

...

My initial consideration was that of LENGTH. If any literary work is too long to be read in one go, the hugely important effect gained from what I call “unity of impression” is lost – for if two or more sittings are required, the affairs of the world interfere and the totality is destroyed. And since no poet can afford to disregard anything that may advance his design, he or she must carefully consider whether there is any advantage to counterbalance such loss of unity. Here I say definitively: No, there is not! What we call a long poem is in fact merely a succession of brief ones – that is, of brief poetic effects. As I shall elaborate below, these effects are apparent to the extent that they intensely excite the soul by elevating it, and all such intense excitements are, by psychological necessity, fleeting. For this reason, at least one half of Milton’s Paradise Lost is essentially prose – a succession of poetic excitements inevitably interspersed with corresponding depressions. And so, due to its extreme length, the whole is deprived of the crucial artistic element of totality, or again, “unity of effect.”

To reiterate, there is a distinct limit of length to all literary works of art: a single sitting. And although in certain classes of prose this rule may be ignored (the episodic Robinson Crusoe doesn’t require such unity, for instance), it can never be breached in a poem. Within this limit, there is a mathematical relation between the length of a poem and its corresponding merit, a measure of the degree to which it excites or elevates. Accepting that a certain duration is required to produce any effect at all, the brevity of a poem is in direct ratio to the intensity of its intended poetic effect.

With these considerations in mind, and not forgetting my goal of writing something not above the popular yet not below the critical taste, I immediately conceived the proper length for my as-yet-unwritten poem to be 100 or instance, lines. In fact, it ended up at 108.

I then moved on to the nature of the impression or EFFECT to be conveyed, again bearing in mind my intention to render a work for the broadest possible audience. Although somewhat beyond the scope of this essay, I have insisted elsewhere that beauty is the only legitimate province of the poem. This should be self-evident, yet allow me to briefly elucidate my real meaning as it has been misrepresented by some of my friends.

The most intense, elevating, and pure form of pleasure is, I maintain, uniquely found in contemplating “the beautiful.” When people speak of beauty they are referring not to a quality, as is often assumed, but to an effect – specifically, to an intense and pure elevation not of the intellect or the heart, but of the soul. And I designate beauty as the particular province of the poem because it is an obvious rule of art that effects should be made to spring from direct causes – that goals should be attained through means best adapted for their attainment – and no one has so far been foolish enough to deny that elevation of the soul is most readily achieved through poetry.

Although to a certain extent the goals of truth (satisfaction of the intellect) and passion (excitement of the heart) can also be achieved in a poem, we can get there far more efficiently in prose. Truth demands a precision, and passion a homeliness (the truly passionate will know what I mean), both of which are totally antagonistic to beauty. This is not to say that passion or truth can’t be profitably introduced into a poem, for they may offer elucidation or aid the general effect by contrast, just as discordancy does in music. But the true artist will always ensure they are subservient to the main aim, and only unveil them in the context of that beauty which is the poem’s true atmosphere and essence.

With beauty as my province, my next question referred to the TONE of its highest manifestation. This was simple: all experience has shown that this is one of sadness. Beauty of whatever kind, of the highest order, invariably excites the sensitive soul to tears, and so melancholy is therefore the most legitimate of all poetic tones.

...

The length, effect and tone decided, I next attempted to deduce a PIVOT upon which the whole structure might turn, some artistic piquancy that could serve as a key note in the poem’s construction. In contemplating all the usual artistic effects, I perceived that the most routinely employed was the refrain. The fact that it was so ubiquitous was enough to convince me of its intrinsic value and spared me the consideration of anything else. I did, however, wonder whether the use of the device could be improved upon, and concluded that it was in a somewhat primitive condition. As commonly used, the refrain is not only limited to lyric verse but depends for its impression upon the force of monotone – both in sound and thought. The effect is gained solely from a sense of identity through repetition. I resolved to diversify and so heighten the effect by sticking to the monotony of the sound while continually varying that of thought. In other words, while the refrain itself would stay the same, I would aim to produce novel effects by diversifying its meaning.

Since the idea was to continuously vary its application, the refrain clearly needed to be brief in nature. The longer the sentence or phrase, the more problematic such variation would be; the shorter the refrain, the easier it would be to adjust the sense without things becoming too convoluted. And so I saw at once that the ideal refrain would constitute a single word. What about the sound? An obvious consequence of adopting the refrain was to divide the poem into stanzas – with the refrain recurring naturally the end of each stanza. To have force, such an ending must be sonorous and afford the possibility of protracted emphasis. These considerations inevitably led me to the long o as being the most sonorous vowel, along with r as the most producible consonant. The sound determined, I cast about for a word to embody it while maintaining that melancholy I had predetermined to be the poem’s overall tone. In such a search it would have been impossible to overlook the word “nevermore” – and in fact it was the very first one that suggested itself to me.

Pondering the difficulty of inventing a plausible reason for its intermittent repetition of the word, I perceived the main trouble arose from the presumption that the word was to be so continuously or monotonously spoken by a human being, i.e., the difficulty lay in reconciling such monotony with the exercise of reason on the part of the creature repeating the word. This led me to the idea of it being spoken by a non-reasoning creature capable of speech. I immediately thought of a parrot, of course, but this was quickly superseded by a raven – equally capable of speech yet infinitely more in keeping with the intended melancholy mood.

I had now arrived at the concept of a raven, the bird of ill omen, monotonously repeating one word, “nevermore,” at the conclusion of each stanza, in a poem of melancholy tone, and with a length of about 100 lines. Now, still never losing sight of my aim of universality, I asked myself: Of all melancholy topics, what, according to the universal understanding of mankind, is the most melancholy? Death was the obvious reply. And when, I continued, is this most melancholy of topics most poetic? Given what I have already explained at some length, the answer here is obvious too: when it most closely aligns itself to beauty. The tragic death, then, of a beautiful woman is surely the most poetic topic in the world – and it is equally beyond doubt that the lips best suited for such a topic are those of a bereaved lover.

I now had to combine the two ideas – of a raven continuously repeating the word “nevermore,” and of a lover lamenting his deceased mistress, along with my intention to vary the application of the repeated word at every turn. The only intelligible mode of such combination involved the raven using the word to answer queries from the lover – and here I saw at once the opportunity this afforded the effect of the variation. Namely, that I could make his first question – the first to which the raven would reply “nevermore” – a commonplace one, the second less so, the third less still, and so on until at length the lover, startled from his original nonchalance by the word’s melancholy character, by its frequent repetition, and by considering the ominous reputation of the fowl that uttered it, would be gradually excited to superstition and wildly start to ask questions of the heart in an increasingly desperate register. He would ask them half in irrational belief and half in that species of despair which delights in self-torture, not altogether because of believing in the bird’s prophetic or demonic character (which reason would assure him is merely repeating a lesson learned by rote), but because he would experience a frenzied pleasure in modelling his questions so as to receive from the expected “nevermore” the most delicious because the most intolerable of sorrow. On realising the opportunity this provided – or rather, forced upon me in the progress of the construction – I first established in my mind the ultimate query to which “nevermore” would be in the final answer, in reply to which this word “nevermore” should contain the maximum amount of regret and despair.

Here then the poem may be said to have its beginning – at the end, where all works of art should begin. And so now I first put pen to paper in the composition of the last stanza:

“Prophet,” said I, “thing of evil! Prophet still if bird or devil!

By that heaven that bends above us – by that God we both adore,

Tell this should with sorrow laden, if within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden with whom the angels name Lenore –

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore.”

Quoth the raven – “Nevermore.”

I assembled this stanza at this point so that, first, by establishing the climax I could better vary and graduate the lover’s preceding queries in terms of seriousness and importance; and second, to settle upon its rhythm, metre, length, and general arrangement, as well as have a basis on which to graduate the as-yet unwritten stanzas that were to precede it, ensuring none of them would surpass it in rhythmical effect. Indeed, if I would have been able to construct more vigorous stanzas in the subsequent composition, I would have deliberately enfeebled them so as not to weaken the climactic effect.

...

Here I may as well say a few words about the poem’s VERSIFICATION – that is, its form or metrical composition. As usual, my first object was originality. The extent to which this has been neglected in versification is one of the most unaccountable things in the world. While we can readily admit there is little possibility of variety in mere rhythm, the possibilities for metre and stanza are infinite – yet for centuries no-one has ever done, or ever seemed to think of doing, an original thing in verse. The fact is, originality – unless in minds of very unusual force – is by no means a matter of impulse or intuition, as some imagine. Rather, to be found it must be elaborately sought after, and although it is a quality of the highest class, its attainment in fact involves more negation than invention.

I do not pretend there is any originality in either the rhythm or metre of The Raven. The former is trochaic (alternating stressed and unstressed syllables), the latter octameter catalectic (8 metrical feet with the last syllable incomplete), alternating with heptameter catalectic (the same with 7 feet), repeated in the refrain of the fifth verse, and terminating with tetrameter catalectic (the same with 4 feet). Less pedantically put, the feet employed throughout (trochees) consist of a long syllable followed by a short: the first line of the stanza comprises 8 of these feet, the second 7.5, the third 8, the fourth and fifth each 7.5, and the sixth 3.5.

Otherwise put:

⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\

⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸

⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\

⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸

⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸

⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸\ ⧸

Now, each of these lines taken individually have naturally been employed in countless other poems; what originality The Raven has is in their combination in stanza. Nothing even remotely approaching this combination has been attempted before. Its effect is aided by other unusual and some altogether novel effects arising from an extension of the application of the principles of rhyme and alliteration.

...

The next point to be dealt with was the MODE of bringing together the lover and the raven, and the first branch of this consideration was the scenario. The most immediate suggestion might seem to be a forest, or in the fields, but it has always seemed to me that a close circumscription of space is necessary to the effect of an insulated incident: it has the force of a frame of a picture, an indisputable moral power in focusing the attention, which should not be confused with mere unity of place.

I determined, then, to place the lover in his chamber – rendered sacred to him by memories of the woman who had frequented it. The room is richly furnished, in accordance with the ideas already explained concerning beauty as being the sole thesis of poetry.

The backdrop portrayed, I now had to usher in the bird. Introducing him through the window was obvious enough, but the idea of making the lover first suppose that bird’s wings flapping against the shutter is a tapping at the door served to increase the reader’s curiosity by simply prolonging it. This, along with the incidental effect arising from the lover throwing open the door, finding everything dark, then adopting the whim that it was the spirit of his mistress that knocked.

I made the night tempestuous, first to account for the raven seeking admission, and secondly for the effect of the contrast with the physical serenity within the chamber.

I made the bird alight on the bust of the Greek goddess Pallas, also for the effect of contrast between marble and plumage. The bust was suggested by the bird, and Pallas specifically as in keeping with the lover’s scholarly character, as well for the name’s sonorous quality.

Around the middle of the poem, I also employed the force of contrast with a view towards deepening the poem’s concluding impression. The raven’s entrance is described with an air of the fantastic, as close to ludicrous as seemed admissible. He comes in “with many a flirt and flutter

Not the least obeisance made he – not a moment stopped or stayed he,

But with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door.

In the next two stanzas, the design is more obviously carried out:

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

“Though thy crest be shorn and shaven though,” I said, “art sure no craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the nightly shore –

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the raven “Nevermore.”

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning – little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door –

Word or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door

With such name as “Nevermore.”

Having laid the ground for the effect of the eventual climax, I immediately drop the fantastic for a tone of the most profound seriousness, beginning in the stanza directly following:

But the raven, sitting lonely on that placid bust, spoke only, etc.

From this point on the lover no longer jests nor sees anything of the fantastic in the raven’s demeanour. He speaks of him as a “grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore” and feels the “fiery eyes” burning into his “bosom’s core.” This revolution of thought or fancy on the part of the lover is intended to induce a similar one in the reader – to prepare the mind for the apotheosis, which is now brought about as rapidly and as directly as possible.

With the climax proper – with the raven’s reply “nevermore” to the lover’s final query whether he shall meet his mistress in another world – we can say that the poem is complete in terms of its rudimentary narrative. So far everything has been within the borders of accountability, the limits of the real. A raven, having learned by rote the single word “nevermore” and having escaped from the custody of its owner, is driven at midnight through the violence of a storm to seek entry at a window from which a light still gleams – the chamber-window of a student, half occupied in poring over a book, half dreaming of his beloved deceased mistress. The casement being thrown open at the fluttering of the bird’s wings, the bird itself perches on the most convenient seat out of the immediate reach of the student who, amused by the incident and the oddity of the visitor’s demeanour, demands, in jest and without expecting a reply, its name.

The raven answers with its customary “nevermore,” which finds an immediate echo in the student’s melancholy heart. Uttering aloud certain thoughts suggested by the unusual occasion, he is again startled by the bird’s repetition. And although perceiving well enough that such reiteration is mechanical, he is regardless impelled by the human thirst for self-torture and superstition to posit further questions designed to bring him the maximum luxury of sorrow via each anticipated answer.

With the indulgence of such self-torture carried to the utmost extreme, what I call the first or obvious phase of the narrative reaches its natural conclusion, and so far the limits of the real have not been breached.

But in subjects handled this way, however skilfully done, or with however vivid an array of incidents, there is always a certain hardness or nakedness that repels the naked eye. Two things are then invariably required: first, some amount of complexity or, more properly, adaptation; and second, some degree of suggestiveness, some undercurrent, however indefinite of meaning. (The latter, especially, affords a work of art a certain richness. The excess of suggested meaning – that is, when manifest as the upper- rather than the undercurrent of the theme – turns the so-called poetry of the so-called Transcendalists into prose of the very flattest kind).

With this in mind, I added two extra stanzas to the end of the poem – their suggestiveness then retroactively pervading all the narrative that has preceded them. The undercurrent of meaning is rendered first apparent in the lines –

“Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore!”

The words “from out my heart” involve the first use of metaphor in the poem. Together with the answer “Nevermore,” they dispose the mind to seek a moral in all that has been narrated. The reader himself now begins to regard the raven as emblematic – but it is not until the very last line of the very last stanza that the intention of making him representative of mournful and never-ending remembrance is finally revealed:

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting,

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the lamplight o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

be lifted – nevermore.

*

(1946 > 2025)